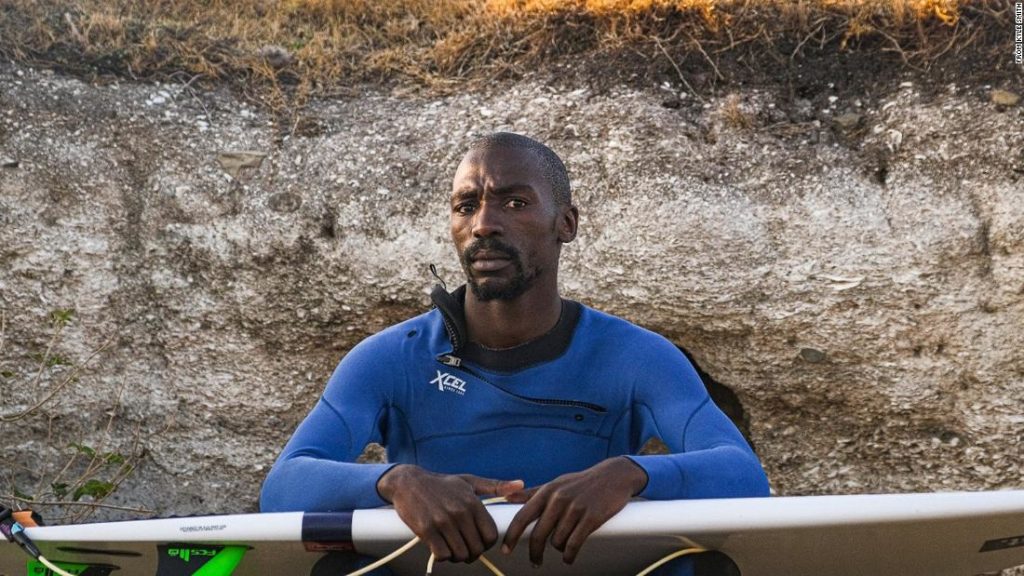

Ndamase didn’t have to travel far with his board; he lived just 300 yards from the water in Port St. Johns, a small town on the Wild Coast in the Eastern Cape province.

Ndamase says he was “super humbled by nature, because — you know — you are just so small,” and he marveled at the natural world around him, learning all he could by watching David Attenborough or National Geographic documentaries on television after school. “I made it a point; I watched it over animation.

“The ocean always provided,” he mused. But it has also taken away. In 2011, Ndamase watched on helplessly as his younger brother, Zama, was killed by a shark.

‘Blood bomb’

If Ndamase is philosophical now, there’s no doubting the trauma he experienced. He says it doesn’t sting anymore, but he prefers not to dwell on the details; however, a few years ago, he described to CNN the sight of a “blood bomb” underwater, “the worst experience of my life and probably will be the worst, ever.”

He stayed out of the water for a while, but when he was ready, nature gave him the tools for rehabilitation, “I didn’t go to much therapy because I had the ocean; the ocean is my therapy.

“You know, for many years, people live in places that are like right by the sea and everything is cool. And then next thing, people are having a tsunami and the ocean will be seen as the enemy. I think the ocean should just be a place that reminds us of how small we are and how we should actually look after each other.”

In 2020, Ndamase celebrated his brother, their relationship and his connection with nature in a short film called “Amanzi Olwandle” (“Ocean Water”).

The three-minute feature, produced by Timothy Way, depicts the two brothers giddy with excitement at daybreak and rushing down to the shore. Zama smiles at his older sibling and runs into the surf, only for the frothing water to turn crimson shortly afterwards.

As an adult, Avo returns to the beach alone, providing the narration that cuts to the essence of his story, “In many African cultures, it is believed ancestors live under the ocean. It is a mysterious place that gives so much and yet can take it all away. A sacred place, and it’s where I find my solitude.”

Producing the film was a nostalgic experience, a return for Avo to simpler times.

“Those kids had the old boards, the raggedy wetsuits,” he recalled. “It really reminded me of where we were growing up. All our friends grew up in the township and we grew up right by the beach, so we had each other to play with every day in the lagoon, running around in the forest, in the mountains.”

The viewer can feel the bond between the brothers, the sadness of the passing, but the celebration of his life, and Ndamase says he can still feel Zama’s presence every time he’s on the board.

He explained, “I’ve had some spiritual people be like, ‘You know, your brother is right beside you every time,’ and I’ve felt it; I do feel like he’s super close to me.”

While he couldn’t protect his brother from the shark, he can sense that Zama is looking out for him. “I know he’s right there, always watching over me. I’m just grateful I had such a person in my life from a young age.”

At the My Røde Reel Awards in 2020, “Amanzi Olwandle” scooped up the $200,000 first prize, beating out entries from 113 countries around the world.

Judge Ryan Connolly praised the film, saying, “Excellent cinematography, rock-solid pace, well-acted, and a ton of heart. It conveyed its emotion and story effortlessly while showing a lot of respect for its audience. I was really floored by it.”

Winning awards had never been the express intention of the project, but the financial windfall was certainly welcome. “It was like a sense of relief because we never really spoke about what would happen if we won. But it was really huge; it helped my family a lot.”

The ocean has always provided.

Free surfing

When surfing makes its debut at the Olympics in Tokyo this summer, there won’t be any athletes who look like Avo Ndamase. In the past, he’s hinted at racism within the sport, but during this interview, he preferred to focus on what he’d like to do with surfing, rather than what he can’t.

The two South African surfers on the World Surf League roster, Jordy Smith and Matthew McGillivray, are White, and there aren’t any Black surfers on either the men’s or women’s tours.

“The representation of African surfing,” Ndamase noted, “is still blond and blue eyes; that’s basically where it’s at.”

He laments that while surfing is growing its platform on the world stage, “It’s not relatable. It’s either a luxury sport for really rich people or super athletes you cannot relate to. You cannot relate to a guy that wakes up every day and goes to the gym and he gets paid a lot of money by all these different companies.”

While Ndamase does have corporate partnerships of his own, such as the clothing brand Vast, he explains there is another side to surfing, less about competition, much more chill, forging connections with the earth and its people.

“There’s a different world to surfing, which is called free surfing, a lot of really cool people traveling the world and experiencing cultures. We try to make surfing a lot more relatable, inviting and welcoming.”

Surfing is how he makes a living, but it’s been less of a career and more of a lifestyle.

“Surfers have always been attached to hippies and if you look at like old hippie photos, there’s a lot of multiracial going on. So, I think that’s what surfing should be like, going back to that old school.

“If I’m on a beach somewhere in Bali, or wherever in the world and I’m just being myself, it’s a lot easier for people to approach me. That’s what’s important, more than the big leagues, you know.”

The most important thing for Ndamase, though, is to protect the environment that he has always loved and respected.

He laments the me-first materialistic attitudes in society, the results of which he has to wade through in the ocean every day.

“It’s really bad; I’m taking so much plastic out of the water.”

He says he tries to clean up the beach every day when he leaves it, but he doesn’t believe that preaching to anybody is going to help solve the problem.

“It’s a work in progress, but we can only fight our own battles and that’s where it gets frustrating. People must see you do it. And then that’s how we make it better. Knock-on effect.”

Avo Ndamase always knew that the ocean was his future; he’ll do what he can to make sure it offers a future to the generations to come, too.

You may also like

-

Super League: UEFA forced to drop disciplinary proceedings against remaining clubs

-

Simone Biles says she ‘should have quit way before Tokyo’

-

Kyrie Irving: NBA star the latest to withhold vaccination status

-

Roger Hunt: English football mourns death of Liverpool striker and World Cup winner

-

‘Every single time I lift the bar, I’m just lifting my country up’: Shiva Karout’s quest for powerlifting glory