Santiago, Chile — In Chile’s arid Atacama desert, Tabita Daza Rojas is trying to scrape together enough money to finish construction on her home before her baby, due anyday, arrives.

Eight hundred kilometers to the south, in La Pintana, a suburb of the capital Santiago, Cynthia González is nursing her 2-month-old boy. But she needs to buy milk to supplement her body’s supply, and is worried about how she’ll afford it.

Without the option to legally terminate their pregnancies, if they wanted to, or any real accountability from the government or the drug companies, the women, represented by the Chilean sexual and reproductive rights group Corporación Miles, are preparing to file a class action lawsuit in the civil courts.

Tabita Rojas’ story

In March 2020, after discovering an ovarian cyst her physician worried could have been caused by her contraceptive implant, Rojas’s doctor at her local health clinic advised she take the pill instead, prescribing Anulette CD.

Rojas didn’t give the switch much thought; she had taken oral contraceptives before and agreed it made sense for her health.

Plus, after giving up her place on a forensic criminology program at 17 because she’d gotten pregnant, the now 29-year-old was once again excited about her future.

“I had to put all that aside and dedicate myself to my son,” said Rojas, who had a second child two years later, and provides for her family by doing seasonal work at a grape packing plant.

By early 2020, however, things were changing. Her children — boys now aged 11 and 9 years old, both with learning difficulties — were more independent, and were spending more time with their father. As part of a government urbanization in her hometown Copiapó, Rojas had been given a small piece of land on which to build a house. She had been saving up money and planned to move out of the home she and her children had been sharing with three other family members.

And, she was in love.

Early on in the relationship, Rojas and her boyfriend had decided not to have children together. “It was going to be impossible to provide for someone else,” she said.

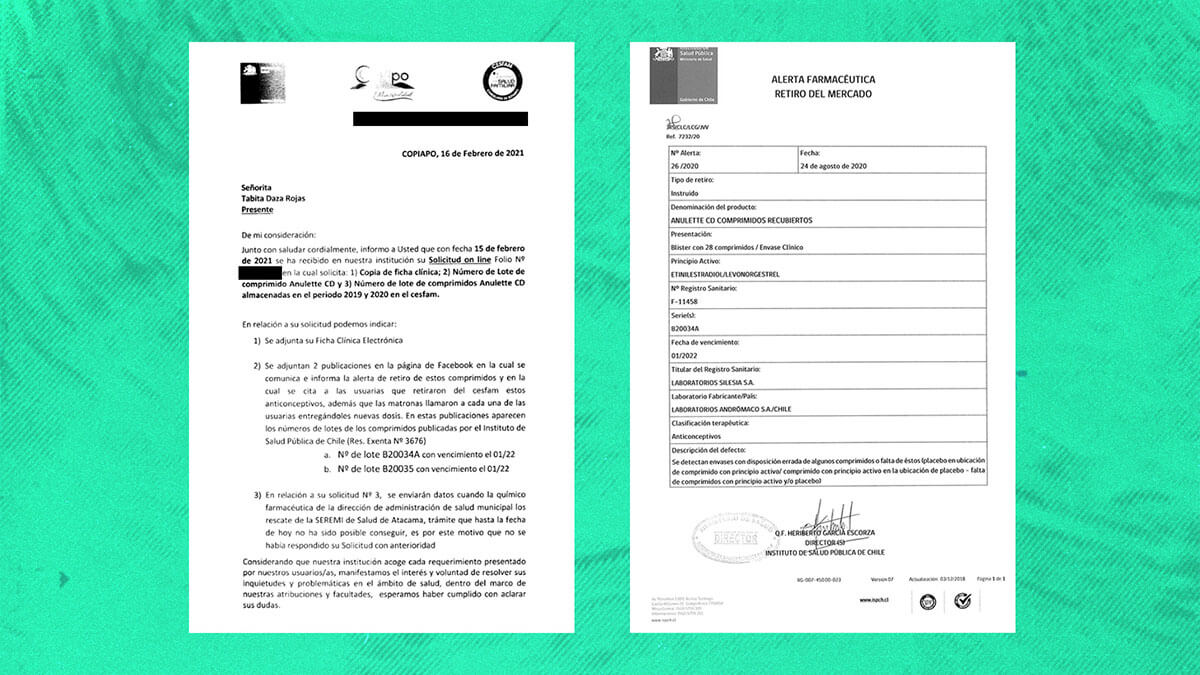

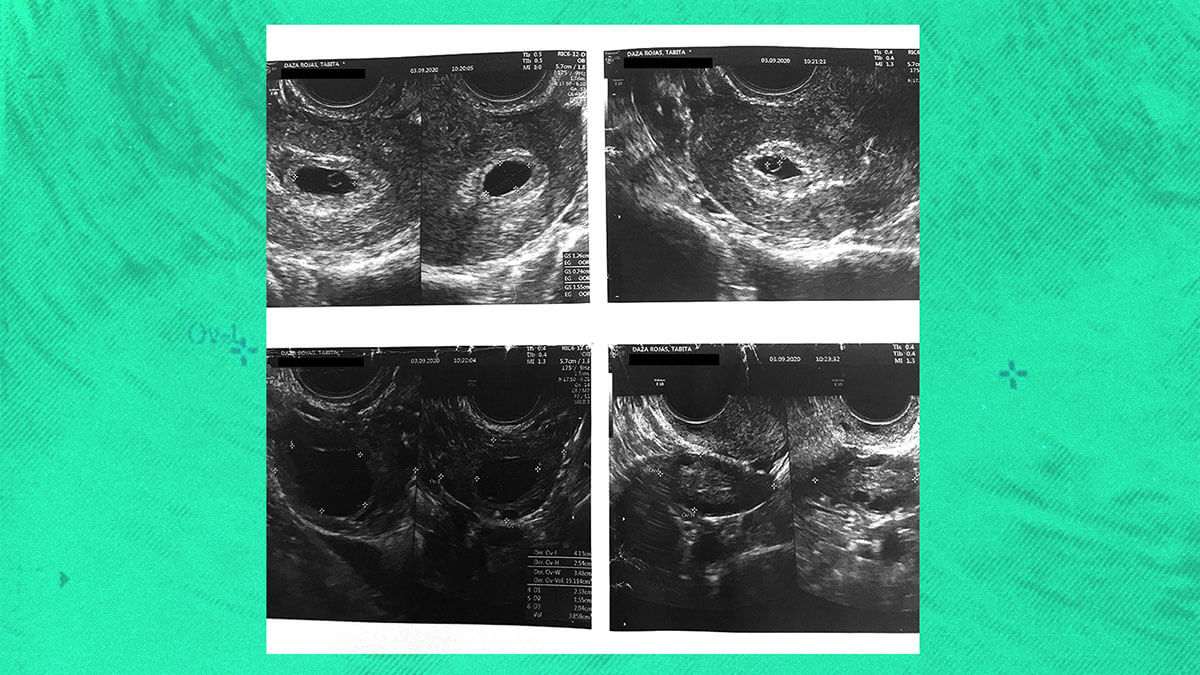

But in September 2020, just five months after Rojas began taking Anulette, she found out she was pregnant again. She would later learn, after seeing it posted on Facebook, that her tablets were from a batch that had been recalled by Chile’s public health authority, the Instituto de Salud Pública de Chile (ISP) the month before.

“I was about to finish the second [box of three prescribed] when I found out about the problem,” she said. By then she was already six weeks pregnant.

‘I was never happy with this pregnancy’

The details may differ but similar scenarios have been playing out across Chile.

A mother of four, González, who had been on Anulette for eight months, got pregnant for the fifth time in May 2020.

She tells CNN that she took her contraceptive “religiously every morning,” before adding: “Because we women set an alarm for those kinds of pills.”

The news devastated her. Her personal life was complicated and her finances extremely limited after she lost the market stall where she sold second-hand clothes.

“I was never happy with this pregnancy,” González said. “If you only knew all the nights I spent crying thinking that I didn’t want to [have the baby]. I had no options.”

“I hid the pregnancy for a long time, so that they wouldn’t ask me: ‘Hey, another child, and whose is it, because you are no longer with your husband’ — and having to explain that we were separated. It was already a complicated situation for me, let alone to go around telling everyone.”

Anulette CD is a 28-day combined oral contraceptive — one of the most common forms of birth control.

It contains synthetic versions of the hormones estrogen and progesterone, which are produced naturally by the ovaries. The hormones work to prevent ovulation — meaning no egg is released by the ovaries — as well as thicken the lining of the cervix to make it harder for sperm to pass through. The pill also makes the lining of the uterus thinner so that if an egg is fertilized it cannot implant and begin to grow.

The first batch — 139,160 packs of Anulette pills, according to its manufacturer — were recalled on August 24, 2020 after healthcare workers at a rural healthcare clinic complained that they had identified 6 packets of defective pills.

In its online notice, published on August 29, the ISP said that the makers of Anulette CD, a company called Laboratorios Silesia S.A. (Silesia), had been made aware and were withdrawing the defective lot. The ISP then advised health centers to quarantine any packets they had from the affected batches.

A week after the first recall, on September 3, the same error was detected in 6 packets from a different batch at a clinic in Santiago. Here, tablets were also missing, but others were crushed, according to the ISP. By the time the problems were flagged, Silesia said it had already distributed 137,730 packs to health centers.

This time the ISP said it would be suspending Silesia’s registration until the laboratory was able to improve its quality and production processes. But it was too little, too late.

In total, according to the manufacturer’s own accounts, 276,890 packets of Anulette CD from the two defective lots — all with a January 2022 expiry date — had been distributed to family planning centers across Chile.

Surprisingly, on September 8, less than a week after Silesia’s suspension, the ISP issued another document reversing its earlier decision. In the memo, which was uploaded to its website, the health authority said Anulette CD could once again be distributed. It claimed that the flaws in the packaging could be easily detected, and passed the responsibility of doing so, and of informing users of the service, onto healthcare workers.

The Ministry of Health told CNN in an emailed statement that they informed the public health service “to inform users of this situation and take pertinent actions,” and said that they provided support and counseling for reproductive health workers to support “women who may have been affected by problems in the quality of contraceptives.”

But Rojas said she was only informed by her local clinic about the defective pills after she went in for a prenatal checkup. And Rodriguez told CNN no one has contacted her.

ISP director Heriberto Garcia defended the decision to put Anulette back on the market, saying in a video interview with CNN: “Just because it [one pack] belongs to the batch doesn’t mean it was bad.”

So, it was left to Chilean civil society to raise the alarm. The sexual and reproductive rights group, Miles, ran a social media campaign and used its networks to get the word out.

“It was after [posting on Instagram] when we started receiving emails from people saying that they were already pregnant because they were consuming Anulette,” said Miles’ legal coordinator Laura Dragnic.

By October 2020, some 40 women had gotten in touch. According to Miles, following multiple media appearances by its staff, another 70 women came forward. The number now stands at 170, but Dragnic expects it to grow as rural women or those without access to the internet or television are still to be reached.

“We expect that there are many more women with this problem,” she said, “especially because the State has not claimed any responsibility and has not made any statements or any serious compromises [to the abortion rules] for the affected women.”

Multiple recalls at Grünenthal’s Santiago factory

In 2017, the company increased its Chilean investments by opening what it called “Latin America’s most modern women’s health products plant” — a US $14.5m facility. While only a small part of Grünenthal’s portfolio, the investment was enough to place it among “the three biggest pharmaceutical companies in Chile.”

But CNN has uncovered that production issues began soon after the factory opened, and have affected a range of oral contraceptives marketed not just by Silesia S.A. but also Grünenthal’s other Chilean subsidiary, Andrómaco.

In 2018, Tinelle, a contraceptive pill from Silesia’s portfolio, was voluntarily taken off the market after a decision to switch the sequence of the active and placebo tablets (keeping the same numbers of each but placing them in a different order) which — by the Grunenthal spokesperson, Florian Dieckmann’s admission — “confused [patients] about the new sequence of the pills.” Dieckmann said that the pills were put back on the market after Silesia “further clarified the instruction on the aluminium foil on how to follow the right sequence of tablets.”

Two further oral contraceptives, Minigest 15 and 20, manufactured by Andrómaco at the Grünenthal Chilean plant, were recalled in October 2020 after the public health authority, the ISP, said that they were found during stability testing to contain an insufficient amount of the active ingredient: the hormones.

Grunenthal’s spokesperson said that at the time of packaging, the tablets had “the correct amount of active ingredient” in them, adding that the “tablets are exposed to excessive temperatures and humidity over the products entire shelf life under laboratory conditions” and that it is “unlikely that the tablets are exposed to these conditions for a long time in real world circumstances.

Based on a Freedom of Information request by Miles, which CNN then followed up on, the production of Anulette CD has had the most problems, according to the ISP’s own records.

Between August 6 and November 18, 2020, health clinics across Chile reported a wide range of issues with the pills including small holes found in the tablets; pills that had orange and black spots; wet and crushed tablets; and packaging that wouldn’t release the entire pill effectively, leaving trace amounts of the pill stuck inside.

In total, the ISP received 26 different complaints about 15 different batches of Anulette pills, yet only 2 batches were recalled.

“It is important to clarify that not all complaints of the products end in market recalls,” the ISP explained. “Those that are withdrawn…are those in which critical defects are detected and this was the case of the recalled batches.”

Aside from publishing details of the above recalls on its website, the ISP allegedly did little else to notify women, and despite its apparent challenges, Grünenthal remains the Chilean government’s leading provider of oral contraceptives.

According to the ISP, 382,871 women are prescribed Anulette CD, and between May 2019 and January 2020, Grünenthal secured at least US $2.2 million in contracts that CNN has seen.

The Ministry of Health did not answer CNN’s written questions and declined an invitation to be interviewed.

The blame game

While no one is denying the production problems, Grünenthal, its Chilean subsidiaries and government representatives, all seem intent on shifting some of the blame away from the faulty packets of the pill and onto each other.

Dieckmann explained that the company discovered that the problems stemmed from an issue on the production line issue which caused some pills to move during the packaging process. That led to some packages with “empty cavities, some tablets misplaced or crushed tablets,” he said but stressed that the efficacy of the contraceptive had not been compromised.

“So I think it’s important background, right?” Dieckmann said, noting that those statistics rise when the pill isn’t taken consistently or correctly.

“I’m not trying to say that it’s the woman’s fault,” Dieckmann said, before adding that correct and consistent use was a “factor that I think we have to look at here.”

“Women say, ‘I was on the pill, I still became pregnant — why is that?’ That’s what’s happened,” he said, referencing the statistics.

The Grünenthal spokesperson told CNN that the company could not speak to their individual cases, as it has not been directly contacted by any of the affected women.

Addressing the controversy on the Chilean public broadcaster in December 2020, Silesia’s medical director, Leonardo Lourtau, said in addition to the company being responsible for visually checking the packaging, health officials should have also done so and, “obviously, the people who take the medicine as well.”

And Garcia of the ISP suggested it was important to look at how birth control efficacy might change when interacting in the body with other products, such as antibiotics, tobacco or alcohol. “I am not saying that she has drunk a lot of alcohol or that she is a smoker, but I am telling you the background.”

‘Systemic failures’

Drug recalls are not unusual, but it is hard for those campaigning on behalf of the women not to perceive an injustice here: Grünenthal continues to see its factory as the key to reaching 168 million women in Latin America, while the women who take its products have to remain vigilant or risk pregnancy. The risk is heightened, reproductive rights groups say, by the fact that these women, already poor and marginalized, can’t count on the robust support of the government should the undesired happen.

Paula Avila Guillen, Executive Director at the New York Women’s Equality Center, a not-for-profit that advocates for and monitors reproductive rights in Latin America, told CNN that if the recall was about bad meat, the entire country would have known immediately, and the product immediately taken off the market. “But when it comes to women and reproductive health, they just don’t care,” she lamented.

And so, Miles and its partners, writing to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and to the United Nations, have called the situation “a clear situation of systemic discrimination against women.”

Meanwhile, back in Copiapó, at 38 weeks pregnant, Rojas has now accepted her fate. She will once again have to put aside her dreams for the future of her child, another baby boy. They’ll name him Fernando.

Edited by Eliza Anyangwe. Additional editing by Meera Senthilingam and Henrik Pettersson. Animation by Melody Shih and Jeffrey Hsu Web, and development by Marco Chacon.

You may also like

-

Afghanistan: Civilian casualties hit record high amid US withdrawal, UN says

-

How Taiwan is trying to defend against a cyber ‘World War III’

-

Pandemic travel news this week: Quarantine escapes and airplane disguises

-

Why would anyone trust Brexit Britain again?

-

Black fungus: A second crisis is killing survivors of India’s worst Covid wave