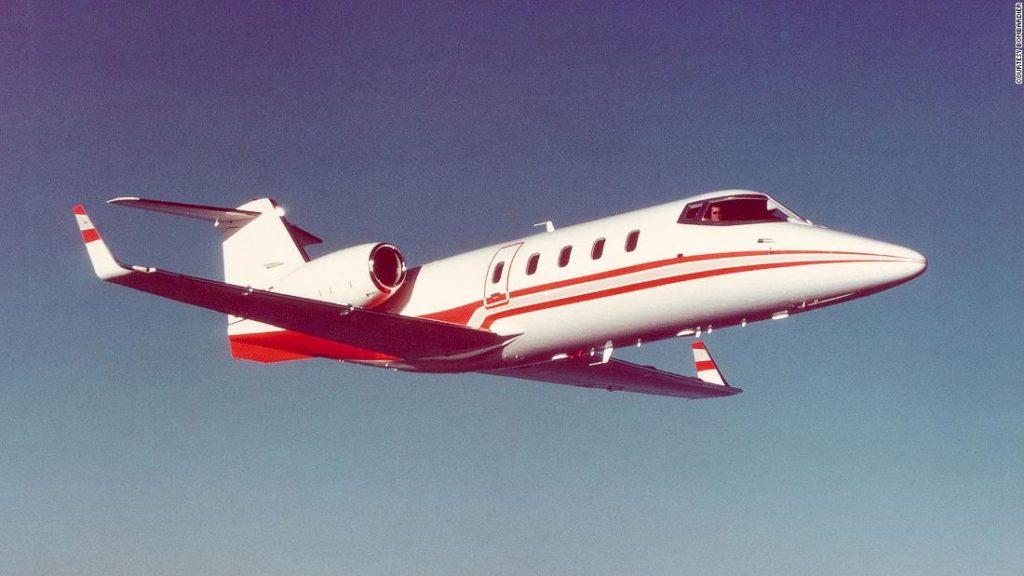

(CNN) — Learjet. For generations, the name has been synonymous with business jets, with more than 3,000 of the small private jet planes delivered since the first Learjet 23 flew in 1963.

In an age when nonstop flights were few, connections long and schedules irregular — and Zoom meetings the stuff of “Star Trek” rather than reality — the Learjet became a must-have for corporations needing to whisk executives around the world, and for Hollywood stars jetting from location to location.

With a purebred lineage from an experimental Swiss fighter jet, Learjets soared 50,000 feet above the earth, taking their name from aviation and electronics pioneer Bill Lear (who would also quickly go on to develop the 8-track tape, a precursor to cassette tapes).

Bigger cabins mean bigger jets — and bigger profits

The Learjet was hugely innovative when it started out, with its neat little airplane cabin giving an experience similar to sitting in a comfortable family car. But as is often the case, bigger was better when it came to business jets.

Criticism of the Learjet — and these are very First Class problems — included its 4’4″ cabin height (1.32 meters). This might have been fine for shorter 1960s executives and celebrities, but isn’t quite up to snuff today. By comparison, Bombardier’s Global 7500/8000 aircraft offer a cabin height of 6’2″ (1.8 meters).

Bill Lear, who died in 1978, is reported to have had a famous response to the critique, though: “You can’t stand up in a Cadillac, either.”

In the 1960s and into the early 1970s, the purpose of business aviation was to save time and hassle for flights within a few hours’ distance, jetting from smaller airfields closer to homes and offices rather than having to sit in traffic to get to the larger commercial airports and then connecting.

For that, people were happy to make the tradeoff of essentially replicating a ride in a comfortable luxury towncar, but zipping through the sky.

But as the global economy changed through the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, so did what private jets needed to do, on the outside and on the inside. As the world became global, so did business aviation — down to the name, with the 1990s’ Bombardier Global Express large business jet arriving on the scene.

Rather than the original Learjet’s sub-2,000-mile range, the latest jets can fly for more than 12 hours for over 6,000 miles, easily across the Pacific. And if you’re flying for 12 hours, and especially if you’re paying the big bucks for it, you want to be comfortable.

The business jet, says Mark Masluch from Bombardier, “went from this tool to get you point to point to, now, really an office, a workspace, or home space in the air where you can seamlessly enter the aircraft and carry on your day as if you were still on the ground.”

Today’s cabins are so big they have zones

Business jet cabins today mean “floating onto a jet, having a completely smooth ride,” explains Masluch. This isn’t just about the structure of the aircraft — as a rule, the bigger the plane, the smoother the ride — “but being able to continue your day, seamlessly, whether it’s connectivity, meal preparation, sleep,” or even in some cases a shower on board.

And a lot of that you just can’t fit into a smaller plane like a Learjet.

“That’s ultimately why we’ve we’ve shifted our focus to the medium and large jets,” like Bombardier’s Challenger and Global families, Masluch says. “Because even people in charter who were entering the space are still looking for that expectation of, ‘well, I can sit on a plane, I have comfort to stand up, I have all the Wi-Fi, I can cook a meal as if I was on the ground, I can have a full lie-flat bed, I can take a shower if I’m on a transatlantic or transpacific journey.'”

These medium and large jets are where Bombardier sees some 90% of business jet revenues, and where it has some 30% of a market where it competes with Gulfstream, which offers its larger G650 family and Dassault, which just flew its biggest business jet, the Falcon 6X.

Large jets like these have three or four zones inside, each with intricately convertible areas with chairs that transform into beds, full-size tables that disappear, “Star Trek”-style swooshing doors, and much more.

The cabins start with a crew area up front with the galley-style butler pantry, then perhaps a club seating space also used for dining, and then more seating that converts into a full double bed, with a lavatory and shower down the back. Of course, it’s all fully customizable for your personal desires, from the color and gloss of every surface to where you want each individual seat.

The next big business jet thing: zero-gravity (sort of)

With big cabins comes extra room for innovation, and there’s some incredible engineering development going on with those 180-degree seats. That’s 180 degrees in multiple directions, mind: not only do the chairs recline to fully flat beds, but they also swivel so you can chat with your assistant in one direction and then rotate for dinner with the family.

But even more angles come into play with Bombardier’s new Nuage seat (that’s French for cloud), which has extra pivot points so the seat sinks you into a zero-gravity relaxation position when you recline.

There’s also the Nuage chaise, where what looks like a sideboard credenza has an articulating cushion structure that converts it from a perching point for meetings or dinner to a fully adjustable chaise longue. It can, of course, also be used as a bed.

It’s all a long way from the Learjet, that’s for sure. But that’s kind of the point: as our world changes, so does the way we travel around it.

You may also like

-

Afghanistan: Civilian casualties hit record high amid US withdrawal, UN says

-

How Taiwan is trying to defend against a cyber ‘World War III’

-

Pandemic travel news this week: Quarantine escapes and airplane disguises

-

Why would anyone trust Brexit Britain again?

-

Black fungus: A second crisis is killing survivors of India’s worst Covid wave