CNN

—

At the western edge of Europe lie two little islands with a complex past.

Ireland and Britain are just 12 miles apart at the Irish Sea’s narrowest point, but waters run deep here – in every sense.

For the past century, Ireland’s northeast corner has been part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

In a bid to improve domestic transport links, the UK government is now conducting a feasibility study to see whether Northern Ireland can be linked by a bridge or tunnel to Scotland, its neighbor over the water. The findings are due later this summer.

The idea is not a new one, but it’s been gaining traction since 2018, when UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson gave the bridge concept his support, and Scottish architect Alan Dunlop unveiled his proposal for a rail-and-road bridge between Portpatrick in Scotland and Larne in Northern Ireland.

More recent arguments – dubbed “sausage wars” – between the European Union and the UK over trade links disrupted by Brexit have added a fresh impetus to the search for a way to create a frictionless route across the water.

The distances involved are short. However, there are geological and environmental challenges so immense this would be one of the most technically ambitious projects in engineering history. There are also questions of economics, infrastructure and entrenched local politics.

The Westminster plans have met with scepticism from local politicians, with Scotland’s First Minister Nicola Sturgeon describing it as a diversion from “the real issues,” while in Northern Ireland, Sinn Féin Deputy Leader Michelle O’Neill called it a “pipe dream bridge.”

Now isolated in Europe, the UK today has a reputation more for burning bridges than building them. However, if it pulls this project off, it could be a wonder to rival the Golden Gate Bridge or the Channel Tunnel. The question the upcoming report must answer is: Can a fixed sea link be done – and is it worth it?

Tom O’Hare

The Giant’s Causeway on the Antrim coast is Northern Ireland’s most visited tourist attraction.

The unique geology of this corner of the world is seen to spectacular effect in the Giant’s Causeway, a Northern Irish UNESCO World Heritage site, and its Scottish counterpart Fingal’s Cave. Legend has it that the countries were once linked by a bridge made of these basalt columns created by ancient volcanic lava flow.

But deep below the surface of this narrow sea you’ll also find Beaufort’s Dyke, a huge 50-kilometer-long natural trench created during the last glacial period. Its average depth is around 150 meters, but at its deepest point, it’s about twice that – enough to submerge the Eiffel Tower.

This dyke lies slap-bang on the most direct route between Scotland and Ireland, and what’s more, it’s the largest known British military dump. There are more than a million tons of unexploded munitions here, as well as chemical weapons and radioactive waste, jettisoned by the UK Ministry of Defence between World War II and the mid-1970s.

On top of this, there are rough seas, strong currents, and the famously unpredictable Irish and Scottish weather. The munitions are the first challenge to the fixed sea link project.

It’s “a considerable clearance campaign,” says David Welch, managing director of bomb and explosives disposal experts Ramora UK: “not impossible, but incredibly challenging.”

He compares the project to trying to recover the most famous product of Northern Ireland’s shipbuilding industry: “It’s a bit like raising the Titanic.”

On an average offshore project, clearance teams might deal with anywhere between one and 10 large munitions a day – so the bill for clearing the trench would run to “many, many millions of pounds” before any construction work could take place.

“We have very strong currents around there,” says Margaret Stewart, a marine geoscientist from the British Geological Survey. The precise location of the munitions aren’t known, as many have been swept north along the seabed, and others never made it to the dyke at all, having been dumped ahead of target by crews cutting corners.

If you’re putting in the foundations for a bridge or tunnel, says Welch, “you need to be confident that the area in which you’re about to place equipment or assets or people is sufficiently clear to allow the safe mooring or positioning of the vessels and everything else.

“What you don’t want is to clear an area around the bridge, only for it to over time have migrated munitions move up against the base of the bridge.”

Liam McBurney/Press Association/AP

View from Torr Head looking towards the Mull of Kintyre.

Building a bridge or tunnel is not just a question of drawing a line between the two closest land masses, explains Paul Quigley, geotechnical engineer and director of Ireland’s Gavin & Doherty Geosolutions. The sea isn’t the blank canvas we imagine it to be.

There’s “existing infrastructure, you’ve got cables, you’ve got shipping lanes,” says Quigley. “When you start to map the seabed, it’s surprising how constrained the resources can be.”

And then when you’re on land, you need to consider the quality of road and rail links, and distances to large population centers. Torr Head in Northern Ireland and Mull of Kintyre in Scotland are the two closest points, but they are remote locations, some way from the key cities of Belfast and Derry in Northern Ireland and Glasgow and Edinburgh in Scotland.

The islands’ biggest cities – Dublin in the Republic of Ireland and London in southeast England – are further away again.

There are three existing ferry routes between the two islands. The Larne to Stranraer ferry connects Northern Ireland and Scotland but its distance from the main hubs means it’s less popular than the busy service between Dublin and the Welsh port of Holyhead.

Says Quigley, “What Brexit has shown is there is a sizable volume of trade that comes into Dublin from (Britain) and it’s destined for Northern Ireland.” He thinks it would be hard to get stakeholders to invest in a route that directs traffic so far north, or for it to be more appealing than the ferry crossings.

“It’s good to dream and good to imagine these things,” he says, but there has “to be a project need.”

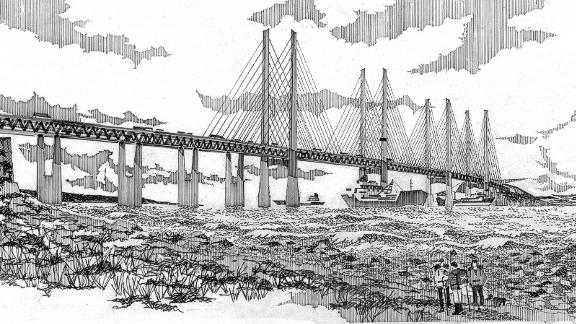

Alan Dunlop

Dunlop admires the iconic potential of a bridge: “something which is risen above the water which reflects excellence in engineering and architecture.”

“There isn’t a major infrastructure project that hasn’t received criticism,” architect Alan Dunlop tells CNN.

He’s studied recent bridge, tunnel, highway and oil rig projects around the world in similarly “difficult geological conditions” and while he admits there’s “none of them as challenging as this,” it’s his firm belief that “within the United Kingdom, we have absolutely the engineering and architectural talent to tackle this.”

He’s made proposals for a “Celtic Crossing” bridge – with an estimated price tag of £20 billion ($28 billion) – and also a sea tunnel. His heart is with the bridge concept, though, as a national symbol and a way of linking the Celtic nations.

His crossing would be a 45-kilometer-long floating pontoon-style bridge anchored to the seabed by cables. He was inspired by oil rigs in the Gulf of Mexico which are connected to the seabed at depths of up to 1,000 meters below.

He says the greatest lessons can be learned from the Norwegian Coastal Highway, a $40 billion, 1,100-kilometer route which connects the country’s west coast.

Its pioneering plans include floating bridges supported by pontoons – a way of handling extreme depths which avoids column contact with the seabed – and the world’s first “floating tunnel.”

A submerged “floating tunnel” tube, attached to surface pontoons or tethered to the sea bed, perhaps in tandem with a bridge, is one of several design propositions in currency.

ANTHONY WALLACE/AFP/AFP/Getty Images

The Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge is the world’s longest sea-crossing bridge.

For the Irish Sea project, “you’re at the outer limits of what is possible from bridge technology,” says Quigley.

“The real constraint on the bridge is the fact that, given the weather conditions, there will be periods when you will close a bridge due to high winds and just the safety aspects. The other issue is you’re putting a structure into a very harsh environment. The maintenance of a bridge structure is likely to be prohibitive.”

While both a multi-span suspension or cable-stayed bridge might be possible, traditional tower supports on the seabed would have to be at a height never achieved before in the world – so more creative solutions have to be found.

China is currently the world leader when it comes to record-breaking bridges. At 48.3 kilometers (30 miles), Hong Kong–Zhuhai-Macau Bridge is the world’s longest bridge over water. It was designed to withstand typhoons and is composed of cable-stayed bridges, an undersea tunnel and its length is broken up by four artificial islands – although the waters there are more shallow than in the Irish Sea.

The world’s longest bridge, at 164 kilometers (102 miles), is China’s Danyang-Kunshan Grand Bridge, while Hangzhou Bay Bridge (36 kilometers or 22.4 miles) spans the greatest expanse of open sea.

Grant Shapps, the UK’s transport minister, told the BBC in March that if a fixed sea link is built, the weather factors mean it’s more likely to be a tunnel than a bridge.

The High Speed Rail Group, a rail industry body, has proposed a sea tunnel between Larne and Stranraer that could bypass Beaufort’s Dyke – but it’s based on plans made by Victorian engineer James Barton 120 years ago. The group also recommended that existing rail infrastructure would need to be improved in both countries to support the tunnel link.

Another bold plan reportedly investigated by UK government officials is a three-tunnel proposition connecting at an underwater roundabout underneath the Isle of Man, similar to the new Eysturoy tunnel network in the Faroe Islands.

Engineer Ian Hunt, meanwhile, has located his proposal further south to make use of the existing infrastructure that supports the current ferry service. He revealed his plans to New Civil Engineer for a bridge and tunnel link, via two man-made islands, between Holyhead in Dublin.

The project is also politically charged, with more support typically coming from Northern Irish and Scottish unionists and less from nationalists.

In Northern Ireland, the bridge’s strongest advocate has been the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), the country’s biggest party, which floated the idea in its 2015 general election manifesto.

The party, which in 2017 struck a deal with the ruling Conservative party which helped prop up the government now headed by Johnson, is currently in disarray, and on its third leader in as many months.

Alan Dunlop tells CNN that reaction to his Celtic Crossing proposal had initially been largely positive, but the Scottish backlash began once Boris Johnson gave public support to the bridge idea at the DUP conference in November 2018.

Nichola Mallon, Northern Ireland’s Infrastructure Minister and a member of the nationalist Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP, told CNN in a statement that it was a “vanity project from Westminister.” Said Mallon, a fixed link “will not provide us with the level of improvement to jobs or trade that some may expect, until we have addressed the longstanding issues within our existing transport network.”

The £20 billion figure is the one that’s bandied around most in discussion around the project, but commentators have speculated that the costs could be much more than that.

Paul Quigley points out that that figure is based on technology associated with the Channel Tunnel between England and France, completed in 1994, but the costs of the Irish Sea project could be much higher because “we’re in a very different era in terms of environmental compliance and risk assessment.”

Then there’s the matter of infrastructure improvements to support the fixed sea link – which will cost money which many on both islands have said would be better used on other community investments.

“it’s difficult to argue on the basis of economics, but it’s not really a project about economics,” Dunlop tells CNN. “It’s about the future of countries and doing something for our kids.”

It’s a bold vision for the future, but it will need a lot of buy-in from the four nations that co-exist in Britain and Ireland.

Like the legend of the Giant’s Causeway, the bridge built by the Irish giant Finn McCool and destroyed in a fight with the Scottish giant Benandonner, it may in the end be a fantastic tale of hubris – but the challenge is not insurmountable.

You may also like

-

Afghanistan: Civilian casualties hit record high amid US withdrawal, UN says

-

How Taiwan is trying to defend against a cyber ‘World War III’

-

Pandemic travel news this week: Quarantine escapes and airplane disguises

-

Why would anyone trust Brexit Britain again?

-

Black fungus: A second crisis is killing survivors of India’s worst Covid wave