But as these Indians struggle to live on a few dollars a day, the country’s ultra-wealthy have gotten even richer and more influential, as their combined fortunes have soared by tens of billions of dollars in the last year.

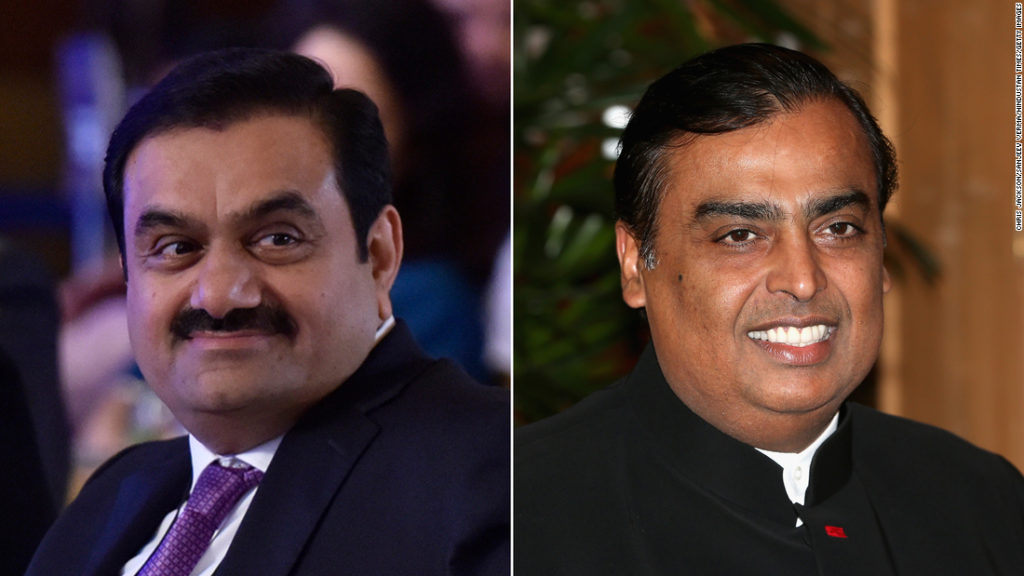

Ambani spent much of the pandemic as Asia’s wealthiest person, ahead of many Chinese tycoons.

Both the Indian billionaires have roots in Gujarat, which is Modi’s home state.

Shares in Adani’s companies tumbled last month after The Economic Times newspaper said that foreign funds that hold stakes worth billions of dollars were frozen by the country’s National Securities Depository.

The utter dominance of Ambani and Adani isn’t surprising, according to Saurabh Mukherjea, founder of Marcellus Investment Managers. He added that almost every major sector in India is now ruled by one or two incredibly powerful corporate houses.

“The country has now reached a stage where the top 15 business houses account for 90% of the country’s profits,” Mukherjea told CNN Business.

“The playbook is the same as other countries,” he said, referencing some of America’s famous tycoons throughout history, including John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie.

The other 99% in India

As India imposed severe restrictions on travel and business activity to control the spread of Covid-19, the share of wealth held by nation’s top 1% rose to 40.5% by the end of 2020, a 7 percentage point increase from 2000, according to a Credit Suisse report on global wealth released in June.

“Meanwhile, the number of people who are poor in India (with incomes of $2 or less a day) is estimated to have increased by 75 million because of the Covid-19 recession,” senior Pew researcher Rakesh Kochhar wrote in a post in March, adding that it accounted for nearly 60% of the global increase in poverty. That increase didn’t account for the second wave.

By comparison, the change in living standards in China has been “more modest,” Kochhar added.

“An alarming 90 per cent of respondents … reported that households had suffered a reduction in food intake as a result of the lockdown,” the researchers wrote in a May report examining the impact of one year of Covid in India. “Even more worryingly, 20 per cent reported that food intake had not improved even six months after the lockdown.”

The Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab has been studying the impact of the pandemic on workers from some of India’s poorest states. In a report on young migrant workers from the states of Bihar and Jharkhand, the researchers found that Covid-19 pushed men out of salaried work, and women out of the workforce entirely.

“They [women] had this one chance of working. Now they are back home with their families and being pushed to get married,” Clément Imbert, associate professor of economics at the University of Warwick and one of the researchers, told CNN Business.

You may also like

-

Afghanistan: Civilian casualties hit record high amid US withdrawal, UN says

-

How Taiwan is trying to defend against a cyber ‘World War III’

-

Pandemic travel news this week: Quarantine escapes and airplane disguises

-

Why would anyone trust Brexit Britain again?

-

Black fungus: A second crisis is killing survivors of India’s worst Covid wave