He knew the proposed plant’s wastewater, ash pit and mercury emissions posed serious health and environmental risks to the local fishing and farming communities. Access to clean drinking water was under threat from the plant’s sulfur dioxide emissions and associated acid rain, and there would have been a clear impact on the regional climate.

Ezekiel, who is from the capital, Accra, was already the founder of an NGO focused on good environmental governance and started what became a successful grassroots youth movement to stop the construction of the $1.5 billion plant, which included a shipping port to bring in coal.

He ran a social media campaign emphasizing the threats of the proposed plans to the environment and local communities, detailing the possible long-term job creation that might come with a shift to renewable energy.

“If the world is trying to move away from environmental destruction because of the fossil fuel, then Africa shouldn’t be seen as perpetuating that era,” said Ezekiel over a webcall.

He was awarded the prestigious Goldman Environmental Prize for Africa on November 30, which honors the achievements and leadership of grassroots environmental activists.

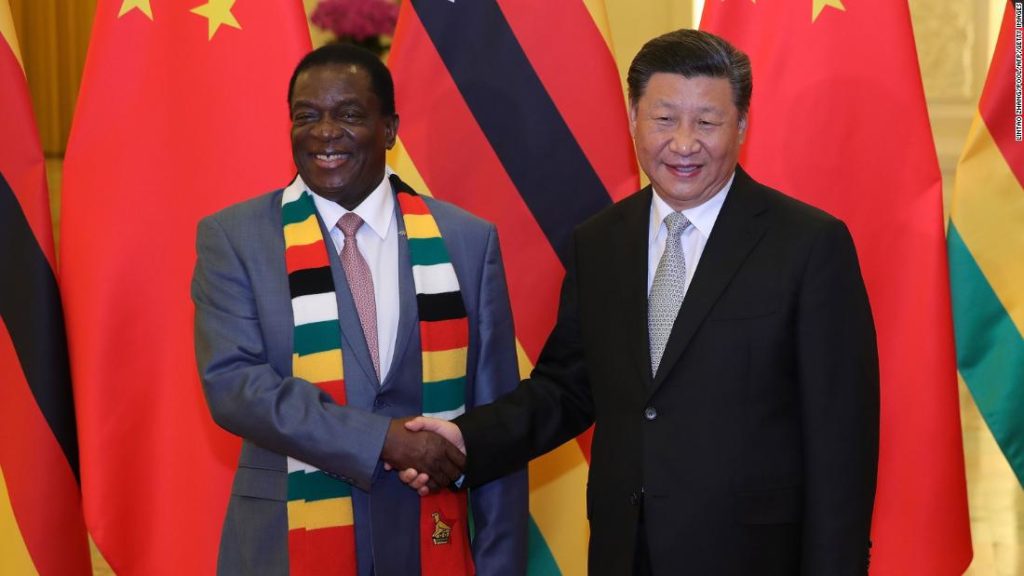

Ezekiel’s victory is but one of many battles raging across the continent between activists, Chinese companies and African governments.

Despite the reputational risk, Chinese companies have continued to finance the construction of coal plants, drawing ire from environmental activists, while African leaders are choosing quick fix solutions to electrify their countries.

China’s dirty belt and road

“Coal has no place in Covid-19 recovery plans,” he said via video link during an online summit hosted by the International Energy Agency (IEA).

But despite these promises to phase out dirty, high-carbon projects at home and abroad, Chinese banks and companies are still financing seven coal plants in Africa like the one planned for the Ekumfi district, with 13 more in the pipeline, mostly south of the Sahara.

It was the China-Africa Development fund that was supposed to finance the coal power plant in Ghana, a private equity fund entirely backed by China Development Bank, a state government policy bank.

Since 2000 the China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China alone have supplied $6.5 billion of finance for coal projects in Africa, according to the Boston University Global Development Policy Center. China has a rapidly developing economy with many sectors dependent on fossil fuels and it currently contributes 26% of global carbon emissions, according to the Green Belt and Road Initiative Center (Green-BRI).

African governments have been happy to push ahead with dirty energy projects that only the Chinese will finance. The potential of a competent energy infrastructure fueled by cheap coal is enticing for a country like Zimbabwe, given the energy deficits slowing economic growth. The country has a national power demand ranging from 2,200-2,400 megawatts but only provides about 1,300, according to the Centre for Natural Resources Governance (CNRG).

Energy shortages and power cuts are commonplace in Ghana, exacerbated by drought conditions because of the country’s dependency on hydro-electricity. Its energy crisis left it vulnerable to energy developers and foreign investment before Ezekiel intervened.

Like other countries investing in Africa, China also promises jobs, while taking advantage of lax policies and cheaper construction costs. Many governments choose to meet the demand for energy at the cost of a clean environment.

This is despite every African country having ratified the Paris Agreement, apart from Angola, Libya, South Sudan and Eritrea.

“Policy on renewable projects is weak or non-existent in Africa,” said Han Chen, the manager of international energy policy at the New York-based Natural Resources Defense Council, a non-profit international environmental advocacy group. “In China, environmental standards are pretty high, while South Africa or Kenya, for example, have energy policies that make it easier for investors to get involved.”

If current plans go ahead, the Chinese-backed coal power output in Africa currently being financed could treble by the time the country realizes its goal of carbon neutrality in 2060, according to Global Energy Monitor.

The Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs did not reply to a request for comment.

Activism across the continent

Ezekiel is not alone in fighting for an Africa focused on renewable energy.

It will receive financial assistance from the construction company China Gezhouba Group Corporation (CGGC), and country risk insurance costs are likely to be covered by the China Export & Credit Insurance Corporation (Sinosure) and the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), according to Global Energy Monitor.

ZELA says the project is shrouded in secrecy and RioZim has not provided information on the environmental or socio-economic impacts of the plant.

When contacted for comment, RioZim replied that “any media engagements are strictly prohibited” under the provision of their “non-disclosure agreements.”

South Africa’s $10 billion, 3,000-megawatt Musina-Makhado power station will be financed by Chinese companies, both state-owned and private, with PowerChina alone contributing $4.5 billion, according to a memorandum of agreement signed in July 2018.

It is part of the proposed Musina-Makhado Special Economic Zone (SEZ) in the Limpopo province north of Pretoria, a mega industrial hub which will span more than 6,000 hectares.

A pre-feasibility study conducted by UK engineering consultancy Mott MacDonald said direct impacts of the site where the coal plant will be located include “detrimental effect on the biodiversity assets of the region,” “disruption of ecological functioning and pollution of water resources” and “large-scale land transformation.” There will be a “definite” release of “significant” greenhouse emissions, according to a preliminary impact assessment.

“The country can’t afford to be locking in to a hugely polluting, expensive and carbon-intensive mega project at a time when — more than ever — we need to act against the climate crisis, protect the resilience of vulnerable, water scarce areas and preserve our limited state funds and resources for projects with positive outcomes and benefits for all,” said Michelle Koyama, an attorney at Cape Town’s non-profit Centre for Environmental Rights (CER).

The Limpopo Provincial Government, PowerChina and the Chinese embassy in South Africa did not respond to requests for comment.

East of Pretoria, Kusile Power Station is being constructed with $2.5 billion from China Development Bank and sponsorship from Eskom, South Africa’s biggest polluter.

The South African environment department launched a criminal investigation against the electric public utility company in May 2019 over air quality concerns at its Kendal Power Station.

Eskom confirmed to CNN that it has been summoned to appear in front of a regional court to answer to criminal charges related to the Kendal plant. These include exceeding the emissions limit on air pollutants and supplying false or misleading information to an air quality officer.

Fossil fuel advocates argue that the energy provided by the plants is vital for development, but centralized coal has failed to deliver electricity to over 2.5 million households in South Africa and can be costly, according to Greenpeace.

“Despite the government promising to provide the people of South Africa with affordable electricity, many of them cannot afford Eskom’s coal-powered electricity — the costs of which continue to escalate,” said Koyama. “Ironically the same communities who live next door to these coal plants, and have to suffer their impacts daily, do not have reliable, affordable electricity in their homes.”

No coal plant brings health benefits and Chinese companies are not alone in receiving criticism for financing their construction.

“Coal investments come with a lot of human rights violations,” Nqobizitha Ndlovu, a constitutional and human rights lawyer who is the legal adviser to ZELA, told CNN in a phone conversation. “There are a lot of complaints here in Zimbabwe, and across all of Africa, that these projects do not respect the right to be healthy, to have a safe and clean environment or the right to water.”

When asked whether they would reevaluate their relationship with Eskom in light of the criminal charges, Deutsche Bank, HSBC and JPMorgan Chase declined to comment.

However while western companies have pulled back from investment in coal plants, Chinese plans are still forging ahead.

“You’re locking a lot of countries into a coal-dependent pathway and the pollution can be horrendous,” said Chen.

A green future

After seeing his 2016 campaign empower communities, Ezekiel is hopeful. He spent four days speaking with chiefs, elders, fishermen and other local groups in Ekumfi, explaining the positives of renewable energy, especially the possibilities for long-term employment.

“We agree that there are people who are unemployed and that jobs are critical,” said Ezekiel. “But we believe that there’s a better alternative in the area of renewable energy which guarantees employment not only for the short term, but for a long time.”

Chen agrees, saying there was “pushback” from communities. “There’s sometimes a disconnect between a national bilateral agreement and what those on the ground actually want,” he said.

Ezekiel launched the Children for Climate Action (C4C) initiative to involve children (as well as young people) in the fight against climate change and the no coal debate. As a national coordinator of 350 Ghana Reducing our Carbon (350 G-ROC), Ezekiel is also encouraging other African countries (particularly Kenya, South Africa and Nigeria) to resist foreign investment in coal.

“A huge mobilization of young people is needed to create more public awareness and education, but we must provide skills and facilities for the youth to be employed, so we can demonstrate that energy indeed provides more job opportunities,” Ezekiel said.

The pan-African activism has had some success and in recent years coal projects have been shelved in Nigeria, Mozambique and Botswana, among others.

CER has successfully stopped the construction of a proposed 557-megawatt plant at Thabametsi alongside environmental organizations Earthlife and Groundwork. It is challenging the environmental authorization for another at Khanyisa, where a water-use licence has already been rescinded.

On the intercontinental stage, Ezekiel is encouraged by the election of Joe Biden as the next president of the United States.

“I would say it is a victory not only for the US, but for the world as a whole,” he said. “He has made comments to the effect that he is prepared to put America back into the Paris agreement. That’s a very big plus.”

China has actually become the largest green finance market, with about 11 trillion yuan ($1.7 trillion) in green credit and about 1 trillion yuan ($150 billion) in green bonds, according to Green-BRI. Growing this market has helped control the pollution and ecological damage resulting from 40 years of extreme economic growth.

Ultimately coal is a fading industry and China is almost alone in financing coal power in Africa. As banks in other countries continue to snub the fuel, it’s likely that Chinese money will build the last ever coal plant.

If the economic behemoth wants to take its commitment to fighting global warming seriously, it needs to stop financing coal plants overseas. For Ezekiel and other activists, the war is turning in their favor.

You may also like

-

Afghanistan: Civilian casualties hit record high amid US withdrawal, UN says

-

How Taiwan is trying to defend against a cyber ‘World War III’

-

Pandemic travel news this week: Quarantine escapes and airplane disguises

-

Why would anyone trust Brexit Britain again?

-

Black fungus: A second crisis is killing survivors of India’s worst Covid wave