The New York native was sentenced in 1992 for the fatal shooting of a man in downtown Buffalo in 1991.

However, his drawings of well-known golf course holes, which he’d never seen before in person, saved him from serving his full sentence.

His first commissioned drawing came at the request of a prison warden after Dixon had spent almost 20 years behind bars. And his rendition of Augusta’s distinctive 12th hole sparked an idea in Dixon, whose appeals had been denied in all courts.

“I realized at some point: ‘Hey, you may have to become one of the greatest artists to ever walk this earth in order to get acknowledgement on what happened to you on this wrongful conviction,'” Dixon told CNN’s Living Golf.

His art helped get him noticed and articles in Golf Digest and other media outlets raised his case to greater prominence in the public’s eye. Thanks to the help of a professor at Georgetown University, Marty Tankleff, and his law students, Dixon reclaimed his freedom 27 years after his wrongful conviction.

“It’s the fight against wrongful convictions and sentencing reform. I didn’t have time to just be all overwhelmed. We got to go to work now,” said Dixon, describing his commitment to turning adversity into a movement to help others.

‘I knew I was innocent’

Life in downtown Buffalo wasn’t easy for Dixon. “It’s [a] kind of dangerous, drug infested neighborhood but you get used to it,” he explained.

He says he found an escape in art. When Dixon was just three, his teacher noticed his talent and helped develop his skill and ability with a pencil; later, he was introduced to a performing arts high school, which he attended until his senior year.

He began redrawing characters from newspapers, as close to the original as possible. Eventually, Dixon says, he believed he got to the point where he was drawing them better than the actual artists themselves.

But on one fateful evening in 1991, Dixon’s life changed.

While he was spending time with some friends at an intersection in Buffalo, a fight broke out in the crowd and someone started shooting. Although one of his friends returned fire, Dixon says he ran to his car and drove away as quickly as possible.

Shortly afterward, he was pulled over by police and asked if he was at the scene of the crime. After admitting he had been, Dixon was taken into custody and charged with murder and for shooting at three other people.

His clothes and car were seized as evidence. He says authorities told him that if he had in fact fired a weapon, they would find gunpowder residue on his clothing.

At the time of his arrest, Dixon “was out on bail awaiting sentencing after he pled guilty in June 1991 to two drive-by shootings,” according to the National Registry of Exonerations.

In the two days following his arrest, eight people came forth with witness accounts that cleared Dixon of anything to do with the crime. The man who actually committed the crime, Lamarr Scott, confessed to police but was “kicked out of the station,” according to Dixon.

Although police disregarded the confession and the witness statements, Dixon says he knew that the results of the gunshot residue testing on his clothes and car would come back negative so he’d be fine.

However, police never produced the results of those tests.

In the end, Dixon appeared in court. “The court had to assign me a public defender and the public defender had in his possession the confession, the videotaped confession of Lamar Scott, the eight eyewitnesses’ statements, and one of the victims that survived, critically wounded victim, [who] told them from his hospital bed that I didn’t shoot him,” Dixon said.

“None of these witnesses made it to court. My attorney did not call one single witness. He didn’t even give an opening statement to the jury. And all of this evidence existed before trial started.”

Subsequently Dixon was handed a lengthy prison term for a crime he didn’t commit.

“I was more concerned about my mom because I’m an only child by her and she was so distraught. I just told her everything was going to be alright,” he said.

“I wasn’t really concerned about myself. I felt in my heart that I was going to get justice, just not at that moment. When you’re innocent of a crime and the evidence is there, eventually justice has to prevail, and this is the mind state that I had at the time.”

Rediscovering his love

Dixon admits for the first seven years of life in prison, he was in a “bubble,” and not in a good head space as he came to terms with his situation.

He says he had fallen out of love with drawing and spent his days “just merely existing, just trying to survive day-to-day.”

Then in his eighth year in prison, his Uncle Ronnie sent Dixon some colored pencils and paper, telling his nephew: “If you can reclaim your talents, you can reclaim your life. You may have to draw yourself out of prison.”

Over time, his love of his art was rekindled. It started with some drawings of Native Americans and flowers from Albuquerque, New Mexico, where some of his family resided.

He says he designed greeting cards — as many as 400 — and another 200 to 300 pieces of artwork.

He was dubbed the “artist of Attica” and came to the attention of a prison warden.

“The warden comes to me and he says, ‘You think you can draw my favorite golf hole before I retire?'” Valentino — who had already served nearly 20 years in prison at this point — recalled.

“I said: ‘You know where I’m from, warden. I’m a Black kid from the inner city. I’ve never golfed before. I don’t know anything about it, but bring a picture in and I’ll draw it for you.’ And it was the 12th hole of Augusta.”

After encouragement from his cell neighbor, Dixon began drawing more golf holes. He would take pictures of holes from magazines and recreate them. He even began creating images of golf courses and holes from his imagination.

He’d spend up to 10 hours a day drawing holes, he says, and then he caught the attention of Max Adler, a journalist for Golf Digest magazine who wrote an article every month titled “Golf saved my life.”

The column featured stories about how golf helped people overcome obstacles they were dealing with and what specifically golf did to make them feel better.

So Dixon wrote to Adler, hoping the journalist would feature a story on his life. And in 2012, Adler wrote a three-page story on Dixon’s ordeal and his drawings.

In Dixon’s words: “It kind of took off from there.”

The release

Tankleff and his class at Georgetown University began discussing Dixon’s case in 2018 in the hopes of helping him regain his freedom.

As soon as Dixon found out that others outside his cell were taking an interest in his life, he knew he wasn’t long for prison.

“You know what? I think this is it. I’m going home now,” he remembers thinking.

Tankleff and his law students were on the phone with Dixon almost every day discussing the case. Eventually, as part of a documentary the students produced on his story, they interviewed the district attorney involved in the case.

“They asked him during the interview: ‘What happened to Valentino’s clothes in his car? I mean, you tested these items,'” Dixon explained.

“And he responded that everything came back negative. It came back negative, but you never turned the results over. That alone is what you call a Brady violation in state law. And because of a Brady violation, you are entitled to a new trial.”

And after a retrial, 27 years after his wrongful conviction, Dixon was a free man again.

The art

Following his “emotional” release, Dixon started a prison reform foundation called the Art of Freedom, which campaigns against wrongful convictions and for sentencing reform.

Although he admits that he’s not a golf fan at all, Dixon was invited to the Masters Tournament and met 18-time major winner Jack Nicklaus, who told the artist that he reminded him of Nelson Mandela because of his “spirit.”

Dixon might even have proved a good luck charm for Tiger Woods in 2019.

“I had a one-on-one [chat] with Tiger for five minutes. I said: ‘Hey Tiger, you’re going to win the Masters.’ He’s looks at me and says: ‘I’m going to try my best.’ I said: ‘No, you’re going to win the Masters.’ And he actually won that year.”

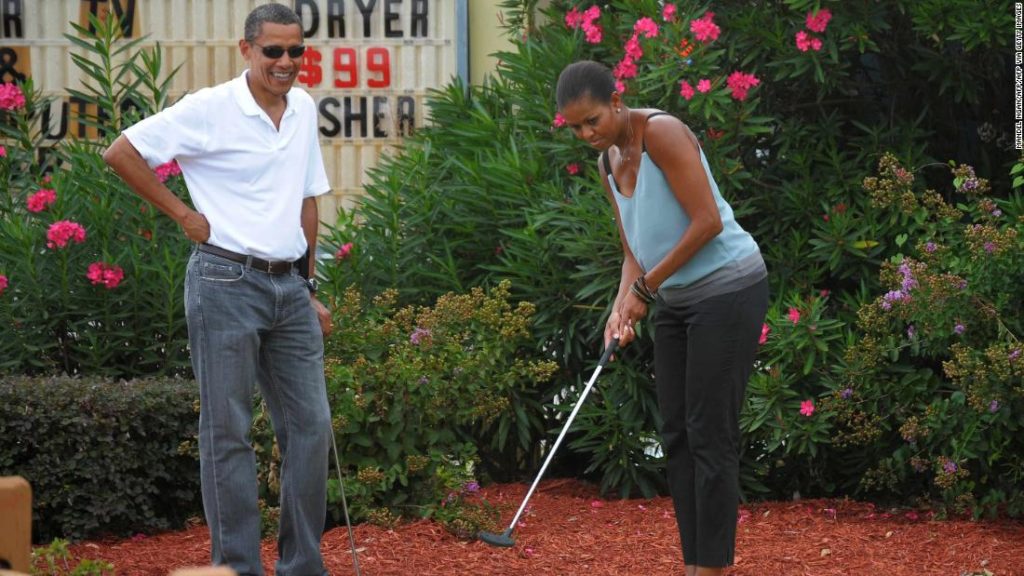

Last year, Dixon also caught the attention of Michelle Obama.

When her office reached out to inquire about a Christmas gift for her husband Barack, who is a keen golfer, Dixon initially wasn’t sure whether it was a hoax. After a bit of checking, he realized the request was genuine and decided the subject of his first-ever golf drawing, the 12th hole at Augusta, would be the perfect present for the former US president.

“It’s an incredible piece, but the story behind it is even better,” it read in part.

Dixon also received a personal video from Obama in which he thanked the artist and said he was proud of him.

It’s the crowning moment of Dixon’s remarkable story, and one which caps his extraordinary journey from being jailed for a crime he didn’t commit to being freed, and becoming a renowned golf artist.

You may also like

-

Super League: UEFA forced to drop disciplinary proceedings against remaining clubs

-

Simone Biles says she ‘should have quit way before Tokyo’

-

Kyrie Irving: NBA star the latest to withhold vaccination status

-

Roger Hunt: English football mourns death of Liverpool striker and World Cup winner

-

‘Every single time I lift the bar, I’m just lifting my country up’: Shiva Karout’s quest for powerlifting glory