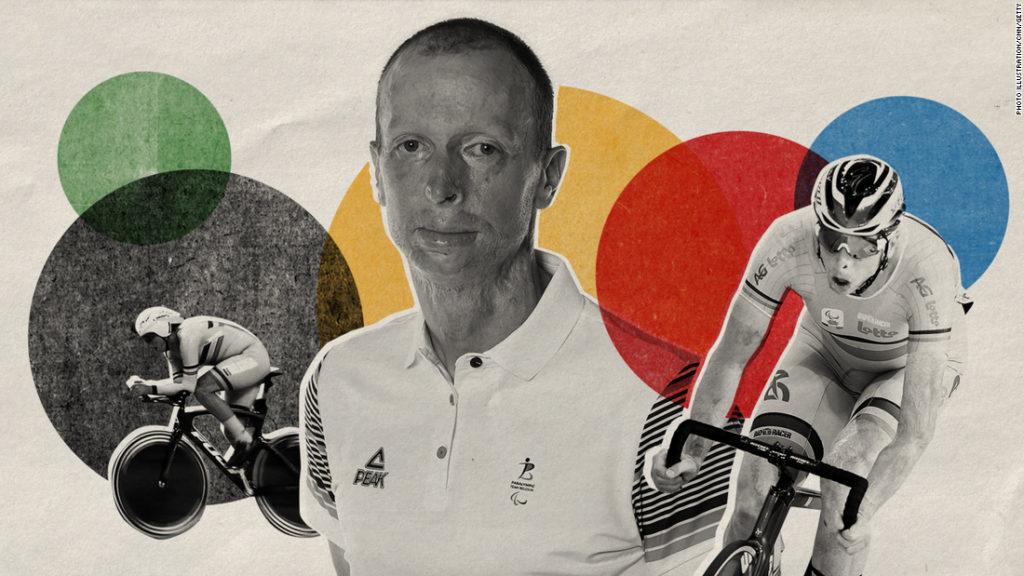

The Belgian cyclist signed his professional contract several months before, working towards his ambition of becoming a pro rider.

It was a goal he had nurtured since he was eight years old, having grown up listening to stories of his father, who had also raced professionally.

But after Schelfhout crashed into a car and then slid into a parked car, his tank burst — and so did that of the vehicle. He was caught between two explosions and says it took firemen 14 attempts to put out the fire.

The aftermath

Schelfhout sustained multiple injuries and 80% of his body was burned, including his lungs.

“I had broken bones, my arm was in pieces, my leg, my hands. It was terrible,” he says.

He spent almost three months in a coma, one that was so severe that his body was going to be put down, but as he puts it, “My heart was strong.”

When Schelfhout did finally wake up he discovered the left side of his body had been left paralyzed by the accident,

When doctors held up a mirror to his face, he could see the physical scarring he had endured. “I take a mirror and they say, ‘Look, this is how you look now and that’s how you’re going to live.'”

As he recalls, his reaction to his new face was “the first mental breakdown.”

“I didn’t think about cycling in the first weeks. I just needed to become stronger,” he says. “I was really into learning, walking again, writing and speaking.”

His friends and family offered him an invaluable sense of moral support, something he still cherishes 13 years later.

“For my parents, it was a really nasty time,” he says, “I’m lucky because my parents are supporting me so hard and so well in everything I do.”

“I have a lot of friends that support me […] I can say I’m a lucky guy. With friends like that and family.”

Fighting to stay in the race

Medical experts eventually told Schelfhout that he needed to shelve his cycling dream, due to the extensive nerve damage in his left leg and his hip.

He says that he decided to try to cycle that same day in order to see what his body might be capable of. “The first 20 meters were the most terrible meters in my life. Everything was hurting, and it was like a child of six years that was trying to bike.”

“The doctors also told me total recovery was not possible.

“I had a girlfriend. She was not into cycling […] and she said, ‘You need to stop everything.’ I told her ‘No, I want to finish what I started, and I stop cycling when I want, not when somebody tells me I need to stop.'”

In the months between his coma and rehab, Schelfhout persisted, using a handbike to improve his upper mobility. After two weeks, he says he had a glimmer of hope, when he observed “some strange feeling” in his bicep. A fortnight later, he had a contraction in his muscle.

Barely a year after his accident, Schelfhout was riding to and from the hospital on his bike.

“I was riding straight to the room of the doctor and I told him, ‘Look I’m back on the bike and I’ll become stronger and stronger and I’m going to race again. I don’t know when, but I have a feeling it’s possible,” he says.

“He told me that it’s my mind that’s so strong. If I want something, I’ll do anything for it.”

A bump in the road

In 2011, Schelfhout’s luck changed when he read a magazine article about Kris Bosmans, a Belgian para cyclist who had started competing after suffering a stroke. Inspired by his story, he decided to reach out to Bosmans.

“At that time, I didn’t think about para cycling because in Belgium it’s not as famous a sport,” Schelfhout says.

However, after hearing more about Bosmans’ story, he began to see para cycling as a pathway to competing.

Determined to race again, he contacted the Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI) — the sport’s governing body — and, in order to get physically ready to compete, he shed over 88 pounds (40 kg) in three months.

His last racing year had been in 2007, so Schelfhout says he was excited about his first para cycling event in 2012 in Rome. “The feeling was nice that I was back on the bike for competition.”

Although, the race didn’t quite go as planned.

Paralympic athletes who use a standard bicycle take part in five sport categories — C1-5 — with lower numbers representing more acute limitation in lower and/or upper limbs.

Schelfhout, who had been placed in the C4 category prior to the race, says he was told before competing that he should have actually been participating in the C3 category.

In his early competition years as a para cyclist, Schelfhout says the most challenging aspect of training and competing was having to reconcile the idea that his body would never be as strong as it was before the accident.

“The first year in para cycling was a terrible year because I was always comparing how I was before the accident and after.”

“For me, the main problem is the nerve problem I have in my left side of my body. My left leg is just a quarter of power compared to the right side, and my arm is one seventh of power.

“My back on the left side is partly paralyzed. I have less power to accelerate.

“There are athletes that before their accident never raced, and they don’t know the possibilities of their body. I know what I could do before and I wanted to do the same.”

Chasing a Paralympic dream

Since then, Schelfhout has been able to regain his confidence by focusing on the mental and physical edge he might have over his peers. For example, he says the right side of his body is stronger than that of able-bodied athletes.

“When I’m competing, there’s like a button in my head, and definitely in big races, that tells me just go for it, just fly and see what you can get.”

In 2016, Schelfhout experienced yet another setback when he had a crash, breaking his collarbone and his hip.

He subsequently found himself left out of Belgium’s first selection for the Paralympic Games in Rio. “After a few weeks, I was back on the bike but I wasn’t in a good condition for racing.”

After four years of working towards a Paralympic dream, he decided to take a break. But two weeks before the Rio Games, he got a phone call from the federation, saying a spot had opened up for his selection.

“I wasn’t in a good shape for the Games,” he says. “Normally on the track if I’m starting, I’m always racing for the podium. Now, I had to make tenth or eighth place. In Rio, I made tenth place. I was not happy about it.”

“Mentally, it was a little bit sad, but it made me stronger.”

When the coronavirus pandemic hit in 2020, Schelfhout says that even though he was disappointed, he felt it necessary to prioritize safety over competing.

“It’s […] better to save our families and friends from the pandemic. It was just one year and one year doesn’t make you worse or better. When you’re at the highest level, you can come back the year after.”

Now, he hopes to make his comeback at Tokyo 2020, where he’ll be competing in four events, including the 3km individual pursuit track race, the 1km time trial track race and the time trial and road race events.

After it all, Schelfhout’s looking forward to representing Belgium at the Games. “For me, it’s a nice feeling, it’s a golden feeling because not everybody can say they can do it. I love my country and I love showing the people of Belgium a great cycling campaign.”

The power of visibility

In retrospect, Schelfhout says mental fortitude has carried him through the most challenging moments of his career.

“Mentally […] I have one slogan, and that’s ‘It’s not how hard you hit. It’s about how hard you can get hit and keep moving forward.'”

“I want to become stronger,” he says. “It’s not about how you look, it’s about how you feel and what you want to achieve and become.”

The best aspect of competing as a para athlete? Schelfhout says it’s finding strength in community.

“I think that’s the nice thing in para sports, everybody is friends with each other because they know how hard life is.”

Since making his way to the world stage, he has dedicated his platform to increasing the visibility of burn victims in sport.

“I want to show people in the world that because you have a really nasty accident, […] you need to still go on in your life. I want to motivate people to play sports again, live again, like before,” he says.

“I have a lot of scars over my body. Everywhere I go, people look at me because a lot of people in Belgium don’t know how people with burn marks look. I want to show them that I don’t care.”

“I want to show that I’m Diederick and I fight for my life, but I still enjoy life.”

‘I am strong enough’

Schelfhout says he wouldn’t have been able to fulfill his childhood dream of being a world class cyclist had it not been for his close knit network of friends and family.

“The people that support me, the federation, it’s really necessary to have good people around you to achieve something good and well in your life,” he says. “I’m so grateful to have that, it’s so important.”

“Everybody around me is really proud of me, but I’m also proud of myself because I have shown the world that I am strong enough to become a cyclist again. I want to show the world it’s possible.”

Competing as a para athlete has given Schelfhout a new sense of respect and gratitude for his body. “I’ve learned that your body and mind is stronger than you can imagine.”

“Before my accident, I always wanted to win. I have the same feeling. But the big difference is when I have a top ten place, I’m also happy. I want to do better. It’s not to say, ‘OK, I’m happy.’ No, but I can understand and live with it.

“I don’t need anything more than my bike, my girlfriend and my dogs to be happy.”

From living through a terrifying accident to undergoing 72 operations, it’s fair to say Schelfhout has been knocked down more than many in life.

But if there’s anything his journey from Belgium to Japan has proven, it’s that the power of getting up, fighting back and maintaining self belief — especially when the odds are stacked against you — will always trump a spell of bad luck.

“When something goes wrong, you need to fight for it.”

You may also like

-

Super League: UEFA forced to drop disciplinary proceedings against remaining clubs

-

Simone Biles says she ‘should have quit way before Tokyo’

-

Kyrie Irving: NBA star the latest to withhold vaccination status

-

Roger Hunt: English football mourns death of Liverpool striker and World Cup winner

-

‘Every single time I lift the bar, I’m just lifting my country up’: Shiva Karout’s quest for powerlifting glory