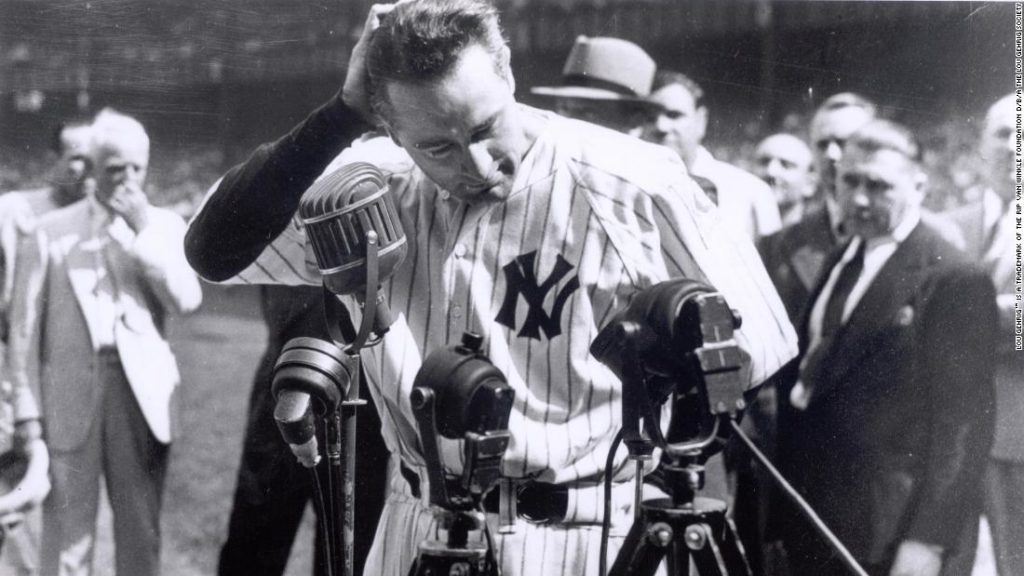

“For the past two weeks, you have been reading about a bad break,” Gehrig told the crowd, his voice thick with emotion, making the last word sound more like ‘brag.’ “(Yet) today I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the Earth.”

Gehrig was an unlikely American hero. The son of poor immigrant parents, he was born in New York in 1903. “If it wasn’t for baseball, he really had very few prospects,” says Jonathan Eig, author of “Luckiest Man: The Life and Death of Lou Gehrig.”

It was at Columbia University in 1921 that Gehrig first discovered baseball. Spotted by a talent scout, he was later signed to the Yankees in 1923.

“He’s the ‘Iron Horse,’ he’s the train: he shows up every day for work,” Eig says.

Despite his Hall of Fame career, Gehrig never sought the limelight, says Eig — and with charismatic and controversial teammates, including Babe Ruth and Joe DiMaggio, Gehrig had little difficulty avoiding attention.

But in 1939, he started missing the ball and took himself out of the line-up. When he was diagnosed with ALS six weeks later, his baseball career officially ended. His retirement came as a shock to teammates and fans alike, and the ceremony on July 4 put the spotlight firmly on him, where he reluctantly took the mic.

“Gehrig told the MC that he didn’t want to speak, that he was too moved to say anything. The crowd began to cheer, began to chant, ‘We want Lou, We want Lou,’ and finally Gehrig’s manager, Joe McCarthy, gave him a little shove and Lou went up to the microphone,” says Eig.

Filled with thanks for his teammates and family, the speech is an exercise in gratitude — “When you have a wife who has been a tower of strength and shown more courage than you dreamed existed,” he said, “that’s the finest I know” — all the more remarkable given what Gehrig was facing.

“There’s a great lesson there for all of us, because we are all going to face tragedy. We are all going to die,” says Eig. “What Gehrig is saying is that it’s not the longevity that counts: it’s the quality of the life.”

Searching for a cure

Activities will vary from stadium to stadium depending on pandemic restrictions, says Falivena, and players, managers and coaches will wear special uniform patches and red “4-ALS” wristbands bearing Gehrig’s retired Yankees’ uniform number, symbolizing a relationship that was cemented on a summer day in 1939 when Gehrig bid farewell.

“I might have been given a bad break,” he told the fans that day, “but I’ve got an awful lot to live for.”

Falivena says that Gehrig and his speech “reflect the community of people with ALS.”

“They are people who, for the most part, are just extremely positive and face this devastating disease with hope, grace, and a fighting spirit,” he says. “I think that relates really well with Lou: he’s not only remembered as a great player, but as a good person.”

You may also like

-

Super League: UEFA forced to drop disciplinary proceedings against remaining clubs

-

Simone Biles says she ‘should have quit way before Tokyo’

-

Kyrie Irving: NBA star the latest to withhold vaccination status

-

Roger Hunt: English football mourns death of Liverpool striker and World Cup winner

-

‘Every single time I lift the bar, I’m just lifting my country up’: Shiva Karout’s quest for powerlifting glory