A seven-time World Series champion with the Boston Red Sox and New York Yankees, and a 12-time American League (AL) home run leader, Ruth played in Major League Baseball from the age of 19 until he was 40.

Ruth was a vaulted star of baseball, the first great sports star in American history. He was baseball’s Michael Jordan before the Chicago Bulls great’s father was even born.

He is undoubtedly a great of the game, yet he played at a time when baseball was segregated.

During first half of the 20th century, the major leagues of baseball were White only.

Consequently, many key Black figures in the early days of baseball in the United States are forgotten.

One in particular, Andrew “Rube” Foster, is considered by many to be the father of Black baseball, and was instrumental in the foundation of the Negro National League in 1920.

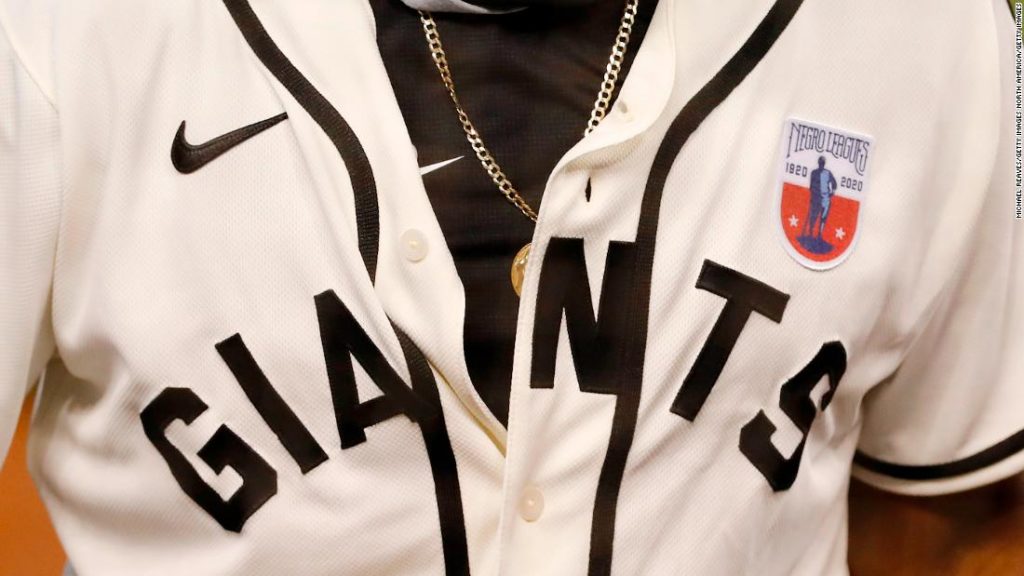

To mark the 100th anniversary of the Negro National League, Turner Sports produced a feature series, entitled “Field of Dreams…Deferred”, which explores the history of Black baseball in the US.

Senior vice president and creative director at Turner Sports’ Drew Watkins told CNN that it was important to tell the story of the Negro Leagues, which has been slowly forgotten over time.

“The exploits of these players in these teams, however great they were, were not told the same way that the exploits of — a lot of times — their white counterparts playing professional baseball were,” Watkins says.

“Everybody knows who Babe Ruth is. Of course, they know who he was. He’s the guy, he’s the best baseball player ever. This is the same time period that we’re talking about. And these players, a lot of them, but if you go by the stories and the accounts, a lot of these players were, you know, as good, if not better.”

The father of Black American baseball

Foster was a terrific player before he became a team owner and league commissioner. Foster had a large build, just like Ruth, but unlike Ruth he was primarily a pitcher rather than batter. In fact, many credit him with inventing the screwball.

Foster was made for bigger things than just playing thought. By 1910 he owned and managed his own team, the Leland Giants — which later became the Chicago American Giants.

A decade on, and after meetings with many different Black team owners, and the Negro National League was formed, with Foster installed as league president.

Black Americans had their own league now, but racism was still rife. And as with contemporary life, racism manifested itself in the economic stability and logistics of the league.

In the series, ‘Field of Dreams…Deferred,’ Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, says “the one fundamental difference” between the Major Leagues and the Negro Leagues was economic.

“Talent? No different,” he says. “But the Major Leagues had more money. And they had their own stadiums.”

Black owners like Foster had to rent stadiums from White teams, which cut into profits. The series later explores the struggle for integration and it is revealed that part of the MLB’s resistance to integration stemmed from White owners not wanting to give up the stadium rent income that was a necessity for the Negro Leagues to pay in order to put on games.

MLB team and stadium owners were profiting off segregation in baseball as long as it existed.

Subsequently, during the early days of the Negro National League, teams were on the road constantly due to not having a fixed home stadium. Teams also needed their own bus as they could not ride trains during a time of segregation.

Many couldn’t stay in hotels as they were for White patrons only. So, they slept on the bus floor. Additionally, they were unable to eat at many restaurants too.

It is estimated in the series by Larry Lester, a Negro League baseball author and historian, that White Major League players earned between six and seven times as much as their Black counterparts in the Negro Leagues.

Despite the social and economic hardship faced by the leagues, they gain popularity and prosper. The first ‘Colored World Series’ takes place in 1924.

A year earlier in the White-only MLB, Ruth won the fourth of his seven World Series titles and his only AL MVP award. In the same year, he won his only AL batting champion title.

History was being made by both Black and White players and organizations in baseball, but society’s overt and covert racism means only a few have been historically valued and kept alive by collective memory.

Watkins says his team wanted to give a platform to keep these stories alive, and remember the Black baseball greats of the past that aren’t held in the same regard as Ruth because of their skin color.

“It’s an important thing to find the people who have the knowledge and to give them a platform to keep these stories alive because all things were certainly not equal,” he says. “And the kind of record keeping and accounting and tracking of these stories, it’s not just you don’t hear about it because they actually weren’t that good. No, they were actually pretty good.

“You didn’t hear about them because of the color of their skin, basically.”

Black empowerment

At the end of the 1920s, further and irreconcilable hardship came with the Great Depression. As Larry Lester puts it, “When we have an economic setback like the Great Depression, White America catches a cold. Black America catches pneumonia.”

Many Black Americans were out of work, so teams had no means of income coming through the turnstiles. Foster dies a year later of a heart attack, and in 1931, the Negro National League folds.

“The death of ‘Rube’ Foster devastated the Negro National League,” Kendrick says. “But then you couple that with the Great Depression and it had virtually no shot.”

The league was later revived and Foster’s impact had taken hold.

While the story of the Negro Leagues of baseball may have been underrepresented in baseball history books, Foster’s significance to Black Americans and the Black community in sport is not and should not be downplayed.

It is not just this accolade where the significance of figures from the Negro Leagues is found though.

For Kendrick, Foster’s story, and the story of the league, is one of economic empowerment and unprecedented leadership within the Black community.

When the Negro Leagues folded following integration, the Black community lost sports team owners, executives and coaches — and with that, the loss of Black role models in positions of power in sport that were not just players.

It isn’t just ownership where Black representation is noticeably low in American sport.

Compared with the NFL and the NBA, the percentage of Black Americans playing in Major League Baseball (MLB) is far lower.

Perhaps that figure would be higher with more Black Americans in positions of power.

By remembering the Negro Leagues and people like Foster, America remembers a story of Black empowerment.

Andrea Williams, author of ‘Baseball’s Leading Lady: Effa Manley and the Rise and Fall of the Negro Leagues’, says as the series closes, “If we were able to accomplish what we were able to accomplish in 1920 with far less resources, what are we capable of now? I think the legacy, honestly, is that we are more powerful than we know.”

You may also like

-

Super League: UEFA forced to drop disciplinary proceedings against remaining clubs

-

Simone Biles says she ‘should have quit way before Tokyo’

-

Kyrie Irving: NBA star the latest to withhold vaccination status

-

Roger Hunt: English football mourns death of Liverpool striker and World Cup winner

-

‘Every single time I lift the bar, I’m just lifting my country up’: Shiva Karout’s quest for powerlifting glory