But the crux of Burns’ narrative is that he wasn’t always revered, in fact, for many years in the United States, Muhammad Ali was dismissed, feared and even despised.

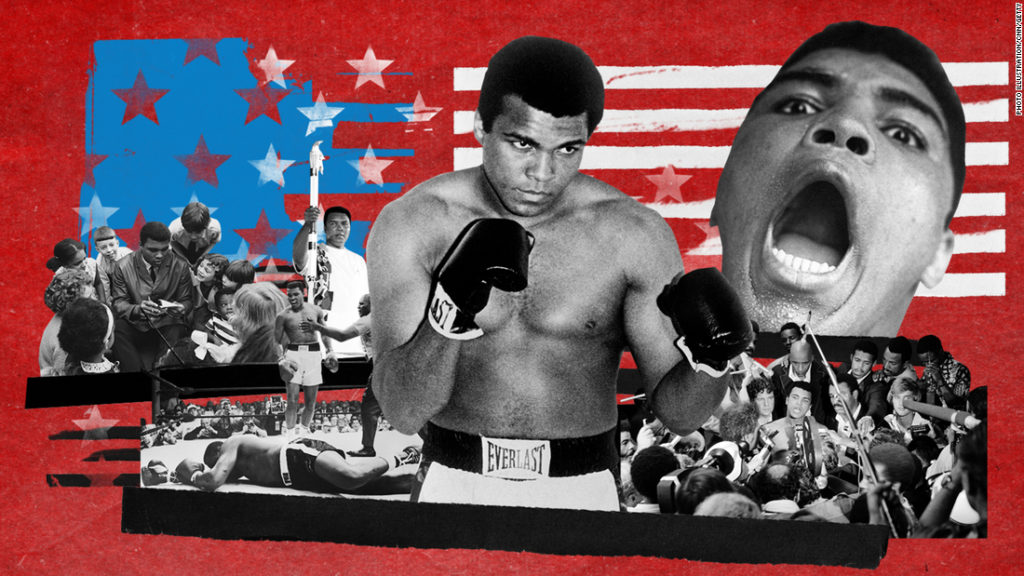

The latter-day image of Ali is that he was flamboyant, loquacious and audacious. A larger than life character who was beloved.

“The biggest misconception about Muhammad Ali is that everybody loved him,” explains ESPN’s Howard Bryant, who is featured in the film. He told CNN Sport, “One of the greatest misconceptions about Ali is that White people loved him from the start. They didn’t. That he belonged to everyone from the start. He didn’t.”

One of Ali’s daughters, Rasheda, told CNN Sport that her father’s life was far from the fairytale that today’s generation might assume it to be. “His life was in danger. He had death threats placed upon him because a lot of people didn’t like him,” she says.

“They didn’t respect him. They thought he was unpatriotic. There was a lot of racism at that time.”

A hero begins his odyssey

From his humble beginnings in Louisville, Kentucky, Burns charts the rise of a promising — if unvarnished — athlete, who was inspired by the civil rights movement of the time.

Born Cassius Clay in 1942, Ali was almost the same age as Emmett Till, the 14-year-old Black boy who was lynched in Mississippi in 1955. According to the film, Ali was said to be haunted by the image of Till’s mutilated corpse, which his mother allowed to be photographed in an open casket at his funeral.

After winning the Olympic gold medal in 1960 and turning professional later that year, Ali often listened to Louis Farrakhan’s 1961 song, “A White Man’s Heaven is a Black Man’s Hell,” but he knew to tread carefully on race because offending his group of all-White sponsors in Louisville might have damaged his chances of landing a title fight.

Throughout the 60s, though, “Gaseous Cassius” began to find his voice, and not just to torment his opponents ahead of their fights. The late Alex Poinsett of Ebony Magazine described him as “a blast furnace of race pride, a pride scorched with the memories of a million little burns.” Additionally, his alignment with Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. ensured that he was viewed with suspicion by the White establishment in America.

But after beating Sonny Liston to become world heavyweight champion in 1964, he saw no further reason to compromise his beliefs, telling the media, “I don’t have to be what you want me to be. I’m free to be what I want and to think what I want to think.” He soon changed his name to Cassius X, and would later change it again to Muhammad Ali and joined The Nation of Islam.

As the new world heavyweight champion, Ali embarked on a five-week tour of Africa and the Middle East and quickly realized the power of his status, but he struggled to find acceptance at home.

“The press is constantly trying to paint him as something other than what he actually is,” explained the civil rights leader Malcolm X at the time. “He is trying his best to live a clean life and project a clean image. He doesn’t smoke, he doesn’t drink. In fact, if he was White, they would be referring to him as the all-American boy.”

In countless film clips and newspaper clippings, Burns’ film reveals a stubborn refusal by many people and organizations to acknowledge Ali by his name. “He’d been Muhammad Ali for ten years, [but] they still called him Clay,” Howard Bryant told CNN. “They were sending their own political message: ‘I am refusing to acknowledge you.’ And that is a powerful attack in and of itself: ‘I am not going to acknowledge your own existence.'”

Defiance

Little Ali ever did, though, was quite as divisive as his refusal to fight in the Vietnam War.

Initially classed 1-Y and disqualified from military service because his writing and spelling skills were sub-standard — “I just said I was the greatest, I never said I was the smartest,” Ali joked — he was then reclassified 1-A and therefore eligible for the draft. Ali poured scorn on the reversal, “Without any test, without checking to see if I’m any wiser,” and he opposed the war on religious and moral grounds, he said in the film.

Ali was now fighting battles on multiple fronts. On February 6th, 1967, he’d tormented Ernie Terrell in the ring because his opponent had refused to recognize his name. Ali’s performance was described by sports writers as “mean and malicious” and “a barbarous display of cruelty.”

But two months later, Ali refused to step forward when his name was called at his scheduled induction into the US military, and according to the film, within hours the New York State Boxing Commission had stripped him of his license, and he was banned from boxing for three years.

He was later sentenced to five-years in prison and a $10,000 fine for dodging the draft.

Ali was unrepentant, “Why should me, and so-called other negroes, go 10,000 miles away from home here in America to drop bombs and bullets on other innocent Brown people?” Ali said that he was prepared to go in front of a firing squad if his punishment required it, “I’m prepared to die,” he says in the film.

In the prime of his career, Ali lost more than three-and-a-half years in the ring, and he resorted to speaking tours on college campuses to make ends meet. He couldn’t box, but he was still fighting.

“He used his tongue to lacerate racism and White supremacy and oppression in America,” said Todd Boyd, professor of cinema and media studies at the University of Southern California’s School of Cinematic Arts.

“He became more militant, not less. He became more assertive, not less. He became more confrontational, not less.”

Ali was addressing Black Panther rallies and anti-war hippies, uniting disparate groups around a common cause.

When he finally got his boxing license back in 1970, Ali was able to expose the racism in America and the folly of the war. NAACP lawyers discovered that the New York State Athletic Commission had licensed 244 boxers who were guilty of crimes far worse than conscientious objection: manslaughter, second degree murder and armed robbery among them.

“We were shocked at the numbers and the range of criminal offenses,” said lawyer Michael Meltsner, “It confirmed our sense that Ali had had been singled out for treatment because of his identity because of his affiliation with the Nation of Islam and because he was a prominent black figure.”

As the anti-war protests grew, Black American men, many who had begun to see themselves as cannon fodder in Vietnam, had slowly become disenchanted and the war was now becoming more universally unpopular in the United States.

“Even the people who disliked him the most at some level had to admit Vietnam was a failure,” Bryant told CNN Sport. “And if Vietnam was a failure, then how you treated him had to be addressed.”

Many of his former detractors now cheered Ali on the comeback trail; against Joe Frazier in 1971 — the first time ever that two unbeaten boxers had fought for the heavyweight title — he made more money in one night at New York’s famed Madison Square Garden than the baseball star Hank Aaron had made in his entire career, according to the film.

But he’d lost some of his speed and had to learn how to take a punch, a strength that would one day become his greatest weakness.

For the first time in his career, Ali lost a fight — a unanimous judge’s decision — after 15 rounds of brutal boxing in the so-called ‘Fight of the Century.’

But, three months later, he got an unexpected victory. The Supreme Court overturned the conviction against him: a shopkeeper ran after him in the street to break the news. In a film clip that was only discovered late in the editing process, Ken Burns says that Ali demonstrated an extraordinary awareness of his place in American history.

Asked how he felt about the court’s decision, Ali told a reporter, “Well, I don’t know who’ll be assassinated tonight, I don’t know who’ll be enslaved or mistreated or deprived of some other justice or equality. All I can talk about is my case. And I’m thankful that the courts recognized my beliefs and my sincerity in this case.”

“He’s thinking about way back for 350 years of the ill-treatment of Black people,” Burns explained to CNN Sport, “He’s thinking about Emmett Till and looking ahead to names he couldn’t have known but knew in his heart would be there like Rodney King, Trayvon Martin, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd. He has this presence, and you realize, my God, he is here for something bigger than himself.”

‘A hero is not perfect’

Two of Ali’s four wives are profiled in the documentary and the producers didn’t shy away from some of the less flattering aspects of his life — his philandering and his cruelty to some of his opponents. “Our superficial media culture today presumes that heroes are perfect,” says Burns, “In fact, the Greeks have told us for millennia that a hero is not perfect.

“He’s a serial womanizer, unfaithful to at least his first three wives and he treats Joe Frazier and several other opponents with a kind of disdain and Jim Crow language that’s inexcusable to my mind.”

However, Burns points out that the women in his life still regard Ali with affection: “You see in their eyes the pain of that infidelity, but the love is still there, there’s a kind of forgiveness and understanding that they had a chance to accompany, for a time, an extraordinary human being.”

“Ali could have $30,000 dollars in his pocket one afternoon and he’d come back with nothing,” said his second wife Khalilah, describing his extreme generosity to those less fortunate than himself. “He just loved to give if somebody was hurting, he loved to help the pain. I think he’ll go to paradise because of that, because he did give a lot to charity!”

His daughter Rasheda described her father to CNN Sport as a gentle soul, a “teddy bear” at home. “My dad was very strong and powerful,” she said, “But my dad was very sensitive. He cried when he would read passages of the Quran, when he would be spiritually connected. He didn’t like going to funerals, it made him really sad.”

“He was such a generous human being,” adds Burns. “In fact, on his gravestone it says, ‘Service to others is the price you pay for your room in heaven.’ And I’ve got to assume he’s got a deluxe suite there.”

The decline that raised a legend

Ali continued boxing in the 1970s, winning two of the most iconic fights of all time, ‘The Rumble in the Jungle’ against George Foreman in Zaire and the ‘Thrilla in Manila,’ a third fight against Joe Frazier.

He was the first to win the world championship three different times and according to the film, earned $50 million, more than all the heavyweight champions combined before him, but the catalog of his ill-advised later fights is painful to watch, depicted in visceral detail on-screen.

In 1980, Larry Holmes landed 340 punches to Ali’s 42, a one-sided fight that left the winner Holmes in tears and stunned the witnesses who were watching from ringside. “It was like watching a train wreck,” said the American journalist Dave Kindred, “Like watching a friend get run over by a truck. As emotional a night as I’ve ever had as a sportswriter.”

Ali fought one more time. It was another one-sided bout against Trevor Berbick in 1981 — three years later he was diagnosed with the disease that would define the rest of his life.

As Parkinson’s disease ate away at his central nervous system, the once quick-footed, fast-talking athlete was now in obvious decline. For a while, Ali was reluctant to admit it, but even he recoiled when he saw a clip of himself on The Today Show. “That man looked like he was dying,” he said.

Perhaps the movie should have ended in 1974, when the underdog Ali outwitted and outboxed Foreman in Zaire. Instead, the denouement is a very different kind of comeback. Ali had been largely forgotten until 1996, when he appeared unexpectedly in Atlanta, shaking but defiant, to light the Olympic flame.

Bryant believes this was the moment that America undeniably fell in love with him: “Because he couldn’t talk [back]. He was safe.” Speaking in the film, Kindred agreed, “He can’t hurt us anymore, he can’t make us mad anymore. The game that we asked him to play to entertain us has left him looking like this. For every reason that we disliked him, now we love him because he was right.”

“You can’t deny this American story,” concludes Bryant. “The thing with these public figures, especially the athletes, is that they are wallpaper for our lives. As they grow, we grow. You start looking and you reflect on your own life and at some point, you have to say, ‘Maybe, he wasn’t the problem. Maybe, I was.'”

You may also like

-

Super League: UEFA forced to drop disciplinary proceedings against remaining clubs

-

Simone Biles says she ‘should have quit way before Tokyo’

-

Kyrie Irving: NBA star the latest to withhold vaccination status

-

Roger Hunt: English football mourns death of Liverpool striker and World Cup winner

-

‘Every single time I lift the bar, I’m just lifting my country up’: Shiva Karout’s quest for powerlifting glory