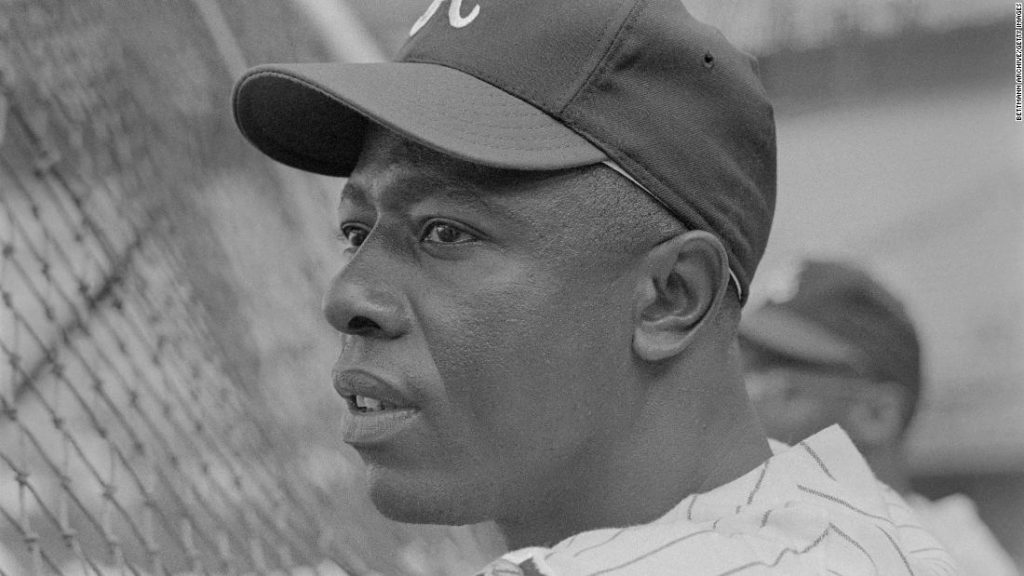

There were the old-school lessons from Herbert and Estella Aaron, his parents in Mobile, Alabama.

I’ll miss the humor.

That’s because Hank smiled easily. Nothing covered dark days with sunshine faster than his contagious laugh, often coming out of nowhere.

I’ll miss the humanity.

Whether it was the work Hank did with his wife, Billye, through their Chasing The Dream Foundation to help gifted youth with scholarships, or just the way he never turned down a request for an autograph or a handshake, he was the most humble sports legend I ever saw.

He became a Braves executive after that. As their farm director during the mid-to-late 1980s, he acquired much of the talent for the franchise’s record run in the 1990s and beyond to 14 consecutive division titles, five National League pennants and a World Series title.

Sometimes, Hank wondered why folks didn’t mention his role during that stretch, but then came that smile.

Then the laugh.

I’ll miss our conversations.

Just a month or so ago, we discussed writing a book.

There were plenty of things this great slugger and even greater person never mentioned about the death threats, the hate mail and the unprecedented racism hurled his way during the early 1970s. Back then, he was racing as a Black man toward shattering the career record 714 homers of Babe Ruth, the Great White Hope for an entire generation.

“I thought I was doomed, you know, but when I got in the batter’s box, I never thought about anything but baseball,” Hank told me during that December conversation, when he added for the first time that in some of the letters writers said they were kidnappers planning to snatch his children.

“The good Lord took care of me in that regard,” Hank continued. “If it hadn’t been for Him, I don’t know what I would have done. Outside of myself, when it comes to going after a record, nobody else had to go through those kinds of things.”

Nobody. Not anybody else who did immortal things with their bat, glove, legs or arms.

Hank paused during our chat last month, adding, “When I think back to those years, yes. I’m disgusted by the things that happened to me.”

He rarely showed it.

Even though Hank kept most of his bitterness toward baseball from his playing days to himself, he wasn’t afraid to blast the game as a Braves executive.

I know, as a sports journalist who has spent his last 36 years in Atlanta, where Hank talked, and I listened.

Then I wrote.

Then I wrote some more.

I wrote about Hank ripping baseball for not having any Black general managers or managers for the longest time before teams hired only a few here, and I wrote about the number of African American players dwindling in the game through the decades to less than 8% these days.

Hank once told me the catalyst for his outspokenness regarding baseball came on October 24, 1972.

That’s the day Jackie Robinson died.

Afterward, Hank said he called other iconic Black baseball players of that time and he told them, “Now that Jackie isn’t around anymore, it’s up to us to pick up the torch and follow in his footsteps for social justice in baseball and everywhere else.”

Hank said he told them that if they didn’t step up, “I’ll just do it myself.”

And did Hank ever.

I’ll miss Hank, period.

You may also like

-

Super League: UEFA forced to drop disciplinary proceedings against remaining clubs

-

Simone Biles says she ‘should have quit way before Tokyo’

-

Kyrie Irving: NBA star the latest to withhold vaccination status

-

Roger Hunt: English football mourns death of Liverpool striker and World Cup winner

-

‘Every single time I lift the bar, I’m just lifting my country up’: Shiva Karout’s quest for powerlifting glory