His longtime team, the Atlanta Braves, said in a statement that Aaron “passed away in his sleep.” The cause of death was not disclosed.

“We are absolutely devastated by the passing of our beloved Hank,” Braves Chairman Terry McGuirk said in a statement. “He was a beacon for our organization first as a player, then with player development, and always with our community efforts. His incredible talent and resolve helped him achieve the highest accomplishments, yet he never lost his humble nature.

“Henry Louis Aaron wasn’t just our icon, but one across Major League Baseball and around the world. His success on the diamond was matched only by his business accomplishments off the field and capped by his extraordinary philanthropic efforts.”

Aaron’s incredible power-hitting achievement came in the face of hate and death threats from people who did not want a Black man to claim such an important record.

Major League Baseball Commissioner Robert Manfred Jr. called his friendship with Aaron “one of the greatest honors of my life” and praised “Hank’s impact on our sport and the society.”

“Hank Aaron is near the top of everyone’s list of all-time great players,” Manfred said in a statement.

“His monumental achievements as a player were surpassed only by his dignity and integrity as a person. Hank symbolized the very best of our game, and his all-around excellence provided Americans and fans across the world with an example to which to aspire. His career demonstrates that a person who goes to work with humility every day can hammer his way into history — and find a way to shine like no other.”

Illustrious career highlighted by 755 home runs

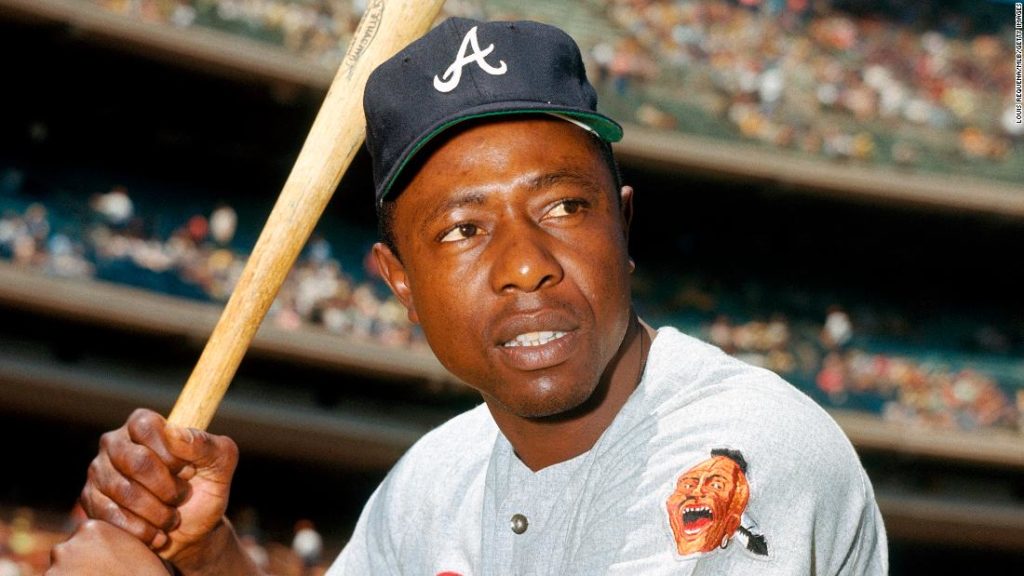

Aaron, known as “Hammer” or “Hammerin’ Hank,” was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1982 following an illustrious MLB career highlighted by 755 home runs — a career record that stood for more than three decades. Aaron famously broke Ruth’s longstanding home run record on April 8, 1974 — hitting his 715th homer at home in Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium.

As he was chasing Ruth’s record, Aaron was taunted daily at ballparks, received threats on his life and was sent thousands of racist hate mail. He said he didn’t read most of the mail but kept some as a reminder.

“There were times during the chase when I was so angry and tired and sick of it all that I wished I could get on a plane and not get off until I was someplace where they never heard of Babe Ruth,” he wrote in his “I Had a Hammer” autobiography.

“But damn it all, I had to break that record. I had to do it for Jackie (Robinson) and my people and myself and for everybody who ever called me a [N-word].”

Former UN Ambassador Andrew Young, who has been friends with Aaron since 1965, said the hate and threats throughout the slugger’s life “rolled off his back like water off a duck’s back.”

“It says a lot about the way his mother and father raised him,” Young told CNN Friday. “He was a child of the South, he was a child of racism, but he never let it bother him publicly. He never let it slow him down or change his focus in life.”

Tributes across the world of sports and politics

Reaction to Aaron’s death and remembrances poured out on Friday from the world of sports and politics.

“The former Home Run King wasn’t handed his throne,” former President George W. Bush said in a statement.

“He grew up poor and faced racism as he worked to become one of the greatest baseball players of all time. Hank never let the hatred he faced consume him. Henry Louis Aaron was a joyful man, a loving husband to Billye, and a proud father.”

Former President Jimmy Carter said the death of their “dear friend” saddened him and his wife, Rosalynn.

“One of the greatest baseball players of all time, he has been a personal hero to us,” Carter said. “A breaker of records and racial barriers, his remarkable legacy will continue to inspire countless athletes and admirers for generations to come.”

The Chicago Cubs tweeted: “A baseball legend who transcended the sport.”

“This is a considerable loss for the entire city of Atlanta,” the city’s mayor, Keisha Lance Bottoms, said in a statement. “Mr. Aaron was part of the fabric that helped place Atlanta on the world stage.”

“Rest in Peace to American hero, icon, and Hall of Famer Hank Aaron,” basketball legend Earvin “Magic” Johnson tweeted.

“We will miss you,” Bernice King, the youngest child of civil rights icon the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. wrote. “Your leadership. Your grace. Your generosity. Your love. Thank you, #HankAaron.”

Hate intensified as Aaron chased Ruth’s record

Aaron’s Alabama childhood was marked by an obsession with baseball. He was kicked out of high school when he cut too many classes to listen to Dodgers games on a pool hall radio.

When Aaron’s hero Jackie Robinson, the first African-American to integrate Major League Baseball, came to Mobile in 1948, Aaron cut class to hear the Dodger speak at a drugstore. Later that day, he told his father that’s what he wanted to do with his life.

Robinson, Aaron wrote in his autobiography, “gave us our dreams.”

“When I was growing up in Mobile, Alabama on a little dirt street, I remember my mother about 6 or 7 o’clock in the afternoon,” Aaron told CNN in 2014. “You could hardly see and I’d be trying to throw a baseball and she’d say, ‘Come here, come here!’ And I’d say, ‘For what?’ She said, ‘Get under the bed.'”

His family would hide under the bed when “the KKK would march by, burn a cross and go on about their business and then she (my mother) would say, ‘You can come out now.’ Can you imagine what this would do to the average person? Here I am, a little boy, not doing anything, just catching a baseball with a friend of mine and my mother telling me, ‘Go under the bed.'”

After leaving high school, Aaron played for the Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro American League.

Years later, with a Class A team based in Jacksonville, Florida, Aaron wrote that the mayor advised him that he should “suffer quietly” when he heard racist shouts from fans.

Fans hurled rocks. They mocked the black players by wearing mops on their heads, and throwing black cats onto the field. The FBI investigated death threats. The players knew to ignore the hate, but “we couldn’t help but feel the weight of what we were doing,” Aaron wrote in his autobiography.

That hate only intensified when he chased the home run record of the venerable Sultan of Swat, as Ruth was known. Hate mail poured into the Braves stadium. The FBI also investigated several death threats and kidnapping plots against Aaron’s children. An armed guard started accompanying Aaron.

“I’ve always felt like once I put the uniform on and once I got out onto the playing field, I could separate the two from say an evil letter I got the day before or an event 20 minutes before,” Aaron told CNN. “God gave me the separation, gave me the ability to separate the two of them.”

He was the first player in an exclusive club

Aaron shone brightly on the baseball diamond. He had 3,771 hits over 23 big league seasons, a milestone he would have still achieved without any home runs, according to the Braves. On May 17, 1970, Aaron became the first player in history in the 3,000-hit, 500-home run club.

The 1957 National League MVP led Milwaukee to a World Series victory that year. He was an All-Star a record 25 times.

Aaron held baseball’s career home run record until he was passed in 2007 by Barry Bonds, whose feat was tarnished by a steroid scandal. Bonds finished his career with 762 homers.

Aaron worked in the Braves front office since retiring from his playing career in 1976 — most recently as a senior vice president, according to the Braves. He founded the Chasing the Dream Foundation, a charity for children, in 1995. He served on the board of the NAACP and was a benefactor of the Morehouse School of Medicine.

“A little bit of Hank Aaron rubs off on you when you get to meet him,” Young said. “His personality was always calm and cool and deliberate.”

In addition to his wife, Billye, Aaron is survived by his five children, Gaile, Hank Jr, Lary, Dorinda and Ceci, according to the Braves organization.

CNN’s Nicquel Terry Ellis and Skylar Mitchell contributed.

You may also like

-

UK coronavirus variant has been reported in 86 countries, WHO says

-

NASA technology can help save whale sharks says Australian marine biologist and ECOCEAN founder, Brad Norman

-

California Twentynine Palms: Explosives are missing from the nation’s largest Marine Corps base and an investigation is underway

-

Trump unhappy with his impeachment attorney’s performance, sources say

-

Lunar New Year 2021: Ushering in the Year of the Ox