He will press ahead in the looming shadow of his predecessor Donald Trump after House Democrats on Monday delivered an article of impeachment relating to his role inciting the Capitol riot.

The uprising, incited by an ex-President who fueled white nationalism, underscored how America’s oldest fault line is also one of its freshest following last summer’s national racial reckoning.

Yet subsequent events have also left a sense that while the country has rarely been more divided since a Civil War that was fought over slavery, progress is possible and as necessary as ever.

‘A moving moment’

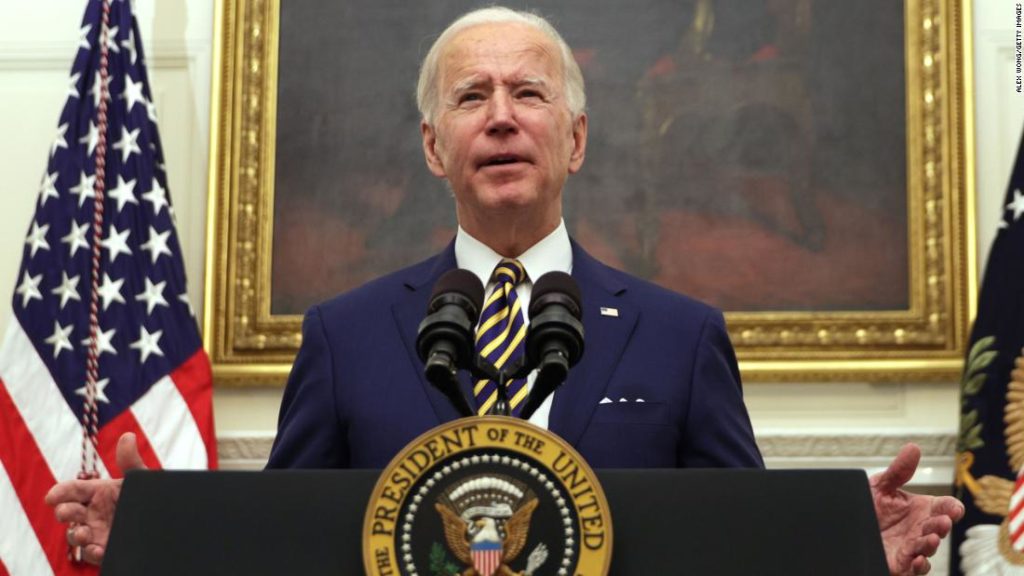

Biden has worked hard to meet the moment, after several clumsy or discordant remarks related to race earlier in his long political career.

During a visit to Kenosha, Wisconsin, during the election campaign, Biden argued that the nationwide tide of emotion that followed yet another shooting of a Black man by police, that paralyzed Jacob Blake, was the catalyst for a new effort to tackle all forms of racism and inequality of opportunity.

He also signaled understanding of the spirit of the resurgent racial justice movement by acknowledging that White Americans could never fully appreciate the historic pain felt by their Black compatriots, an experience shared by many other citizens.

“I can’t understand what it’s like to walk out the door or send my son out the door or my daughter and worry about just because they’re Black they may not come back,” Biden said.

Soaring words and symbolism are important — they are part of a President’s armory in mobilizing the public and affecting political change. But alone, they cannot transform a country or the lived reality of African Americans. The limited social mobility of millions and the busted promises of many previous “conversations about race” sometimes seem little changed from the reality noted by Martin Luther King Jr. in his book “Where do we go from here: Chaos or Community” that was first published in 1967.

“Loose and easy language about equality, resonant resolutions about brotherhood fall pleasantly on the ear, but for the Negro there is a credibility gap he cannot overlook,” King wrote.

In a more recent lesson, the presidency of the first black commander in chief Barack Obama shows that the very act of breaking down barriers that at the time can seem epochal and irreversible can incite new prejudice and breed extremism.

What Biden plans to do

Biden’s effort will require action from the Justice Department to tackle civil rights abuses and to guarantee fairness in the judicial system for all. Former national security adviser Susan Rice has a new White House job, leading the Domestic Policy Council, which includes racial equity among its sweeping menu of responsibilities.

Biden on Tuesday will sign executive actions establishing a commission on policing, partly in response to the death of Minnesota man George Floyd with a policeman’s knee on his neck last year.

He is also expected to order improvements in prison conditions and to mandate the Department of Housing and Urban Development to promote equitable housing policies.

Last week, in the first hours of his presidency, Biden signed an executive order requiring all government departments to put racial and other forms of equality at the center of everything that they do during his term.

One, established that “advancing equity for all — including people of color and others who have been historically underserved and marginalized — is the responsibility of the whole of our government.” Biden also countermanded an earlier executive order signed by Trump.

Like much of Biden’s presidency, his capacity for action, and to secure the massive funding that serious reform requires, will be constrained by narrow majorities in Congress and Washington’s fractured political scene in the post-Trump era. But he does have the moral authority of having won office against a President who tore at the nation’s racial chasm with a hard line “law and order” campaign based on false claims that the Democratic nominee wanted to dismantle policing as it is currently known.

Biden in the middle

Like many other issues, the debate over what Biden has said is “systemic” racism in the criminal justice system puts the President between two absolutist positions. He finds himself confronted on his right by conservatives keen to demagogue him as anti-police and an enemy of White heartland values.

Conservative media has already accused Biden of wrongly equating every Trump voter with White nationalists and racists. And many Republicans are now seeking to draw false equivalence between the Trump-inspired violence on January 6 in Washington and clashes that broke out during Black Lives Matter protests last year. Biden has condemned violence in all cases. And violence that erupted in the summer in many cities was not the true expression of the attitude of millions of people who marched to protest racial injustice. The attack on the Capitol represented an unprecedented assault on another branch of government by a US President trying to steal an election.

To his left, Biden is confronted by progressives who want sweeping reform — some of whom defined the term “defund the police” that many party leaders say helped cost Democrats victories in some key swing state races in the House.

This particular issue also pulls Biden between two versions of his own political persona. He was severely criticized for his role in 1990s criminal justice legislation that ushered in mandatory minimum sentences that sent many young Black men to jail for years. But he has also always had a strong relationship with the police and their unions during his long political career.

But the shocking events of last summer and the long litany of videotaped examples of police brutality against African Americans have irrevocably shifted the potency of race and policing in the Democratic Party. And Biden’s positioning, though obviously sincere, is also enforced by political reality.

Still, some of Biden’s longtime contacts in policing have told CNN that his experience and familiarity with both sides of this most difficult issue may uniquely equip him to oversee a policy response that goes some way to reconciling the extraordinary, and multi-racial national protests after Floyd’s death.

You may also like

-

UK coronavirus variant has been reported in 86 countries, WHO says

-

NASA technology can help save whale sharks says Australian marine biologist and ECOCEAN founder, Brad Norman

-

California Twentynine Palms: Explosives are missing from the nation’s largest Marine Corps base and an investigation is underway

-

Trump unhappy with his impeachment attorney’s performance, sources say

-

Lunar New Year 2021: Ushering in the Year of the Ox