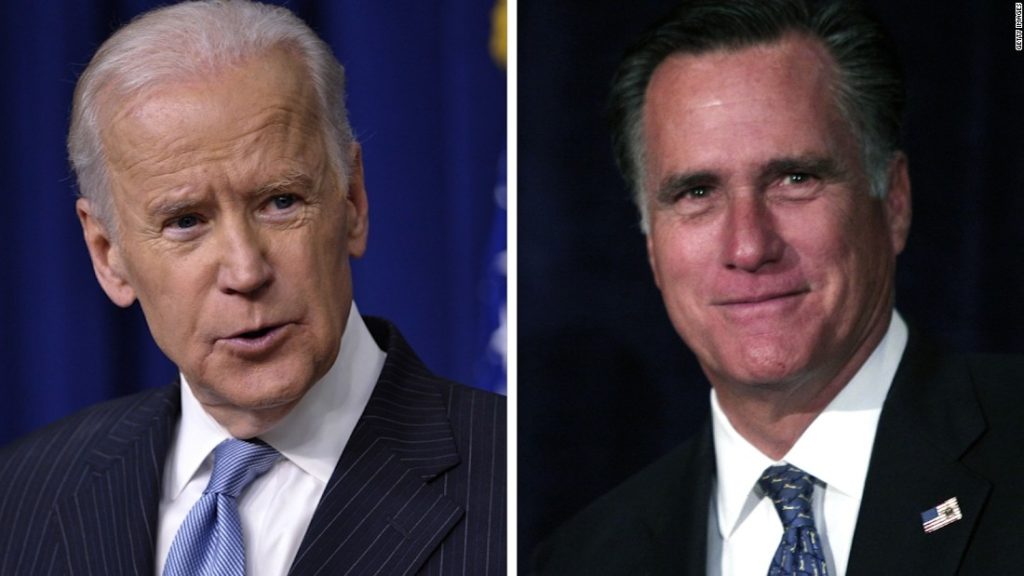

The two were on opposite sides of the Presidential ticket in 2012, though, as Romney recalled to CNN on Tuesday, that didn’t stop Biden from speaking at Romney’s 2017 political summit.

“He was kind enough to come and speak at my conference in Utah, and we spent probably an hour together, with our wives, and had a very nice meeting. Seems like a very down-to-earth, charming guy,” Romney said.

With 36 years in the US Senate, Biden will have more experience on Capitol Hill than any other US President. Yet only a quarter of those he served with are still in Congress, meaning he will have to rely on a few key relationships to get things done. Along with maintaining working partnerships with the leaders of both chambers, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, Biden will have to rely on a handful of moderates and close political allies.

Here are the most important relationships to watch between Biden and the Hill early in his administration.

Chris Coons

One key ally of Biden’s will be the man who now occupies his Senate seat, Democrat Chris Coons of Delaware. A friend for more than 30 years, Coons remains an unofficial adviser in regular touch with Biden and his team.

According to a senior Democratic Capitol Hill aide, during the transition Coons has spoken with incoming White House counselor Steve Ricchetti daily and incoming White House chief of staff Ron Klain multiple times a week.

Regarded as temperamentally moderate and willing to work with Republicans, Coons will be a reliable barometer for his fellow senators about where the new President will stand.

“He is trusted from them to be an emissary,” said the Democratic aide. “And I think people know in the Senate, if Chris Coons is coming to you with an idea, it’s something the (Biden) White House will get behind.”

For Biden, Coons will be just as important for taking the temperature of any group of centrist senators who might hold the balance of power over presidential nominations, spending bills or big pieces of legislation.

Joe Manchin

There was a time when Joe Manchin was the Democrat least welcome by the Obama White House. The West Virginia senator often found himself voting against the administration on issues like climate, trade and guns. And by the second term, Manchin was in regular contact with only one Obama administration official: Biden.

“Manchin didn’t have a great relationship with anybody in the Obama administration except for Joe Biden,” said the Democratic Hill aide. “Biden was the only person (at the White House) that Manchin would call, and the only person who would call Manchin.”

Biden eventually became a key adviser to Manchin on a gun control bill he co-wrote in 2013, drawing on his own experience crafting gun legislation. At one point, Manchin asked Biden to stop the White House from publicly supporting the legislation — which would have killed any momentum to get GOP support.

“Biden kept the White House from endorsing it, from saying anything about it,” said the Democratic aide.

Manchin could also help Biden build a bridge to Trump voters. West Virginia is the second-most pro-Trump state (behind Wyoming), giving Manchin insight into a slice of Trump’s base of working-class white voters who continue to move away from the national Democratic Party.

If Biden hopes to regain ground with these voters, he could do worse than to keep calling Manchin.

Lisa Murkowski

There’s also space for a Republican centrist contingent. Sens. Romney, Susan Collins of Maine, Pat Toomey of Pennsylvania and Rob Portman of Ohio could all at times provide crucial votes in breaking from their party. But Alaska’s Lisa Murkowski could be the most crucial partner for Biden on that front.

Murkowski is up for reelection in 2022, meaning she’ll have cross pressures from both her right within the Alaska GOP as well as from centrist voters who have occupied her base of support for two cycles.

On social issues and with respect to judicial appointments, Murkowski has been the most willing Republican senator to break with the Mitch McConnell and the GOP conference — an opportunity for the Biden administration.

But given the challenges from conservatives she has faced in her state in her last two reelection efforts — a successful primary challenge in 2010 that forced Murkowski to run as a write-in candidate in the general, then a strong Libertarian party challenge in 2016 — Murkowski will need to be careful in choosing her battles.

That may give Biden some insight into where this crucial GOP vote in the Senate may be most sensitive.

James Clyburn

Perhaps no single person is more responsible for Joe Biden’s presidency than Rep. James Clyburn. His endorsement before South Carolina’s primary earlier this year revived Biden’s struggling campaign by delivering Black voters across the South.

It was the first step to Biden securing the nomination, but it didn’t end there. Clyburn has also taken some credit for encouraging his pick for running mate, Sen. Kamala Harris.

The most senior Black lawmaker in Congress and the third-ranking House Democrat, Clyburn is in a strong position to continue influencing Biden on both personnel and policy. Days after Biden’s election, Clyburn told CNN he was speaking frequently with the transition team.

“From all I hear, Black people have been given fair consideration,” Clyburn told Williams. “I want to see where the process leads to, what it produces. … But so far it’s not good.”

Nancy Pelosi

The speaker of the House will have a much narrower Democratic majority next January, giving the progressives in Nancy Pelosi’s caucus a relatively louder voice. Some of those voices on the left, including Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, are already directing their rhetorical fire at the likes of Manchin, presaging a potential civil war between Democrats.

Pelosi’s task is once more to keep her House caucus in line, but she will be aided by having a fellow Democrat in the White House again. By maintaining a positive working relationship with Pelosi, Biden may be able to redirect some of the internal energy into legislative productivity.

He and Pelosi have a long history of working together on big legislation, first in their shared years in Congress and then during the Obama administration in passing the stimulus and Affordable Care Act. Pelosi also worked with Biden to help secure House Democratic support for the Iran nuclear deal.

An aide to Pelosi told CNN that she and Biden are “cut from the same cloth.”

Mitch McConnell

In the final days of the Obama administration, with Biden presiding over the Senate floor for the last time, members gave a send-off to the outgoing Vice President. Mitch McConnell, the Republican Senate majority leader who had served alongside Biden for 24 years, spoke first in a tribute both to the man himself and their positive working relationship.

McConnell said he trusted Biden “implicitly” and praised the Vice President as a negotiating partner.

“There’s a reason ‘Get Joe on the phone’ is shorthand for ‘Time to get serious’ in my office,” McConnell said.

There’s also a risk the majority leader’s silence on Trump’s baseless claims of election fraud could chill relations with the incoming President. McConnell has only been willing to say that the “process” of the election will play out and has yet to acknowledge Biden as the President-elect.

But after Biden is inaugurated, the Kentucky Republican may be ready to get serious again. McConnell’s ruthless pragmatism suggests an opportunity for Biden to find areas to work with him. Some of the groundwork is already being laid for confirmation of a number of Biden’s proposed Cabinet nominees, with Republican senators offering praise for some members of the announced national security team.

In the end, McConnell’s interest will ultimately be in protecting and growing his majority. That will limit Biden on everything from judicial nominations to big legislative packages. So much of what the next two years look like will depend on how willing McConnell will be to “get Joe on the phone” and make a deal.

CNN’s Ted Barrett contributed to this story.

You may also like

-

UK coronavirus variant has been reported in 86 countries, WHO says

-

NASA technology can help save whale sharks says Australian marine biologist and ECOCEAN founder, Brad Norman

-

California Twentynine Palms: Explosives are missing from the nation’s largest Marine Corps base and an investigation is underway

-

Trump unhappy with his impeachment attorney’s performance, sources say

-

Lunar New Year 2021: Ushering in the Year of the Ox