It was a tragedy for Francis I of Brittany when his wife Yolande of Anjou died in 1440. But she was soon replaced — both as his wife and in her own prayer book, where her image and coat of arms were painted over and replaced with those of her successor.

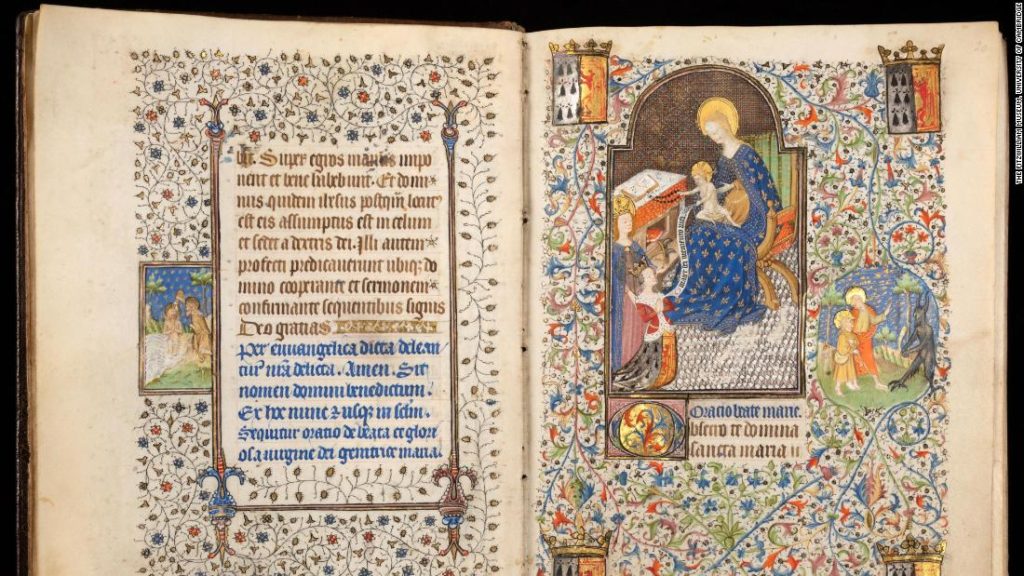

Yolande had appeared as a tiny figure kneeling before the Virgin Mary on one of the most glorious pages of her magnificent “Book of Hours,” now one of the treasures of the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, UK.

Within two years of her death, Francis had married Isabella Stuart, the daughter of James I of Scotland, and — as new research by the museum proves — even before then, the marriage craftsmen were obliterating Yolande’s image.

Original underdrawings shows a kneeling figure of the Duke’s first wife, Yolande, wearing a headdress. Credit: The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge

The spectacularly illuminated book, with more than 500 jewel-like miniatures, was originally commissioned by Yolande’s mother, a patron of the arts who also owned another famous “Book of Hours”: the “Belle Heures of the Duc de Berry,” now in the Cloisters of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

The book was probably given to her daughter upon her marriage to Francis in 1431. Analysis of the original pigments through use of infrared photography, by scientists at the Fitzwilliam, has revealed the under drawings underdrawings and different pigments used to prepare the book for the new bride soon after Yolande’s death.

Isabella’s face and ermine-trimmed heraldic robes were painted over Yolande, and the figure of St. Catherine added behind her. Isabella’s coat of arms was added to the floral borders, using the same vermilion red as her gown, which the analysis distinguished from the red lead paint of the original.

Isabella originally wore Yolande’s elaborate headdress, but around the time of her marriage this was altered again, overpainted with azurite to give her a golden jeweled coronet, marking Francis’ succeeding to the title of Duke of Brittany.

Francis and Isabella had two daughters before his death in 1450, and she outlived him by almost half a century. The manuscript was altered yet again for Isabella’s daughter Margaret, who added an extra page with an image of herself kneeling in prayer before the Virgin.

The last private owner was Richard Fitzwilliam, an Anglo-Irish nobleman who never married but had three acknowledged children by a Parisian ballet dancer, and left his astonishing library of paintings and manuscripts as the museum’s founding collection on his death in 1816.

You may also like

-

Afghanistan: Civilian casualties hit record high amid US withdrawal, UN says

-

How Taiwan is trying to defend against a cyber ‘World War III’

-

Pandemic travel news this week: Quarantine escapes and airplane disguises

-

Why would anyone trust Brexit Britain again?

-

Black fungus: A second crisis is killing survivors of India’s worst Covid wave