Imagine, if you will, the most glorious festive feast, with an oversize turkey, stuffing two ways, holiday ham, the requisite fixings and at least half a dozen pies and cakes. That may all sound grand — that is, until you consider the extravagant displays of the ancient Roman banquet.

Members of the Roman upper classes regularly indulged in lavish, hours-long feasts that served to broadcast their wealth and status in ways that eclipse our notions of a resplendent meal. “Eating was the supreme act of civilisation and celebration of life,” said Alberto Jori, professor of ancient philosophy at the University of Ferrara in Italy.

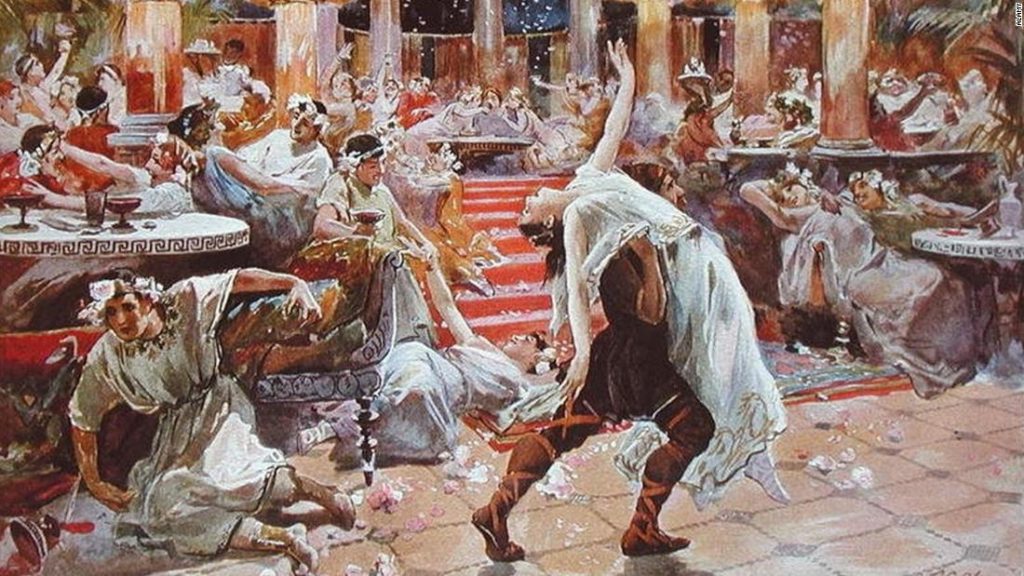

‘The Roses of Heliogabalus’ by Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1888) depicting Roman diners at a banquet Credit: Active Museum/Alamy

What’s more, hosts played a game of one-upmanship by serving over-the-top, exotic dishes like parrot tongue stew and stuffed dormouse. “Dormouse was a delicacy that farmers fattened up for months inside pots and then sold at markets,” Jori said, “while huge quantities of parrots were killed to have enough tongues to make fricassee.”

Among the unusual recipes prepared by Conte is salsum sine salso, invented by the famed Roman gourmand Marcus Gavius Apicius. It was an “eating joke” made to amaze and fool guests. The fish would be presented with head and tail, but the inside was stuffed with cow liver. Clever sleight of hand, combined with shock factor, counted for a lot in these competitive displays.

Bodily functions

Gorging for hours on end also called for what we would consider untoward social behavior in order to accommodate such gluttonous indulgences.

“They had bizarre culinary habits that don’t sit well with modern etiquette, such as eating while lying down and vomiting between courses,” Franchetti said.

These practices helped keep the good times rolling. “Given banquets were a status symbol and lasted for hours deep into the night, vomiting was a common practice needed to make room in the stomach for more food. The ancient Romans were hedonists, pursuing life’s pleasures,” said Jori, who is also an author of several books on Rome’s culinary culture.

It was, in fact, customary to leave the table to vomit in a room close to the dining hall. By using a feather, revelers would tickle the back of their throats to stimulate the urge to regurgitate, Jori said. In keeping with their high social status, defined by not having to engage in manual labor, guests would simply return to the banquet hall while slaves cleaned up their mess.

An engraving of a banquet at the house of Lucius Licinius Lucullus from around 80 B.C. Credit: Ullstein Bild/Getty Images

Gaius Petronius Arbiter’s literary masterpiece “The Satyricon” captures this typical social dynamic of Roman society in mid first century AD with the character of wealthy Trimalchio, who tells a slave to bring him a “piss pot” so he can urinate. In other words, when nature called, revelers didn’t necessarily go to the bathroom; often the WC came to them, powered again by slave labor.

The comforts and privilege of wealthy men

Bloating was reduced by eating lying down on a comfortable, cushioned chaise longue. The horizontal position was believed to aid digestion — and it was the utmost expression of an elite standing.

“The Romans actually ate lying on their bellies so the body weight was evenly spread out and helped them relax. The left hand held up their head while the right one picked up the morsels placed on the table, bringing them to the mouth. So they ate with their hands and the food had to be already cut by slaves,” Jori said.

2nd century A.D. mosaic depicting an unswept floor after a banquet Credit: De Agostini/Getty Images

Lying down also allowed feast goers to occasionally doze off and enjoy a quick nap between courses, giving their stomach a break.

The act of reclining while dining, however, was a privilege reserved for men only. A woman either ate at another table or knelt or sat down beside her husband while he enjoyed his meal.

“Men’s horizontal eating position was a symbol of dominance over women. Roman women established the right to eat with their husbands at a much later stage in the history of ancient Rome; it was their first social conquest and victory against sexual discrimination,” Jori explained.

The emperor Nero participating in a bacchanalia Credit: Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group/Getty Images

Superstitions at the table

The Romans were also very superstitious. Anything that fell from the table belonged to the afterworld and was not to be retrieved for fear that the dead would come seek vengeance, while spilling salt was a bad omen, Franchetti said. Bread had to be solely touched with the hands and eggshells and mollusks had to be cracked. Were a rooster to sing at an unusual hour, servants were sent to fetch one, kill it and serve it pronto.

Feasting was a way to keep death at bay, according to Franchetti. Banquets ended with a binge-drinking ritual during which diners discussed death to remind themselves to fully live and enjoy life — in short, carpe diem.

In keeping with this world view, table objects, such as salt and pepper holders, were shaped as skulls. According to Jori, it was customary to invite beloved dead ones to the meal and serve them platefuls of food. Sculptures representing the dead sat at the table with the living.

A mosaic of a skeleton from the House of Vestals in Pompeii holding jugs of wine Credit: Werner Forman Archive/Shutterstock

Wine wasn’t always drunk straight but spiked with other ingredients. Water was used to dilute the alcohol potency and allow revelers to drink more, while seawater was added so that the salt preserved wine barrels coming from faraway corners of the empire.

“Even tar was a common substance mixed with the wine, which over time blended with the alcohol. The Romans could hardly taste the nasty flavour,” Jori said.

Perhaps in the ultimate symbol of excess, the epicure Apicius allegedly committed suicide because he had gone broke after throwing too many lavish banquets. He left behind, however, a gastronomic legacy, including his famous Apicius pie made with a mix of fish and meat such as bird interiors and pig’s breasts. A dish that might struggle to entice at modern feasting tables today.

You may also like

-

Afghanistan: Civilian casualties hit record high amid US withdrawal, UN says

-

How Taiwan is trying to defend against a cyber ‘World War III’

-

Pandemic travel news this week: Quarantine escapes and airplane disguises

-

Why would anyone trust Brexit Britain again?

-

Black fungus: A second crisis is killing survivors of India’s worst Covid wave