There is a lot we do not know, but the broad consensus from experts and law enforcement in this field is that less space for extremists online is a good thing. Yet there are pertinent questions as to how the far-right have adapted and will adapt their message online to avoid scrutiny and further deplatforming. Certainly, also, there is no precedent for the deplatforming of the world’s most powerful man — no sense of what it might mean.

(To be clear, I am not comparing ISIS to the US far-right or to Trump supporters generally — such direct comparisons are clumsy, far-fetched and ultimately lazy — but the deplatforming campaign waged against ISIS is a rare direct parallel to what is happening now, and it is worthexamining how lessons learned from its online rise and fall might be useful in combating US domestic terrorism).

Twitter and other platforms would have periodic — and sometimes urgent — purges in which accounts would vanish. A former senior US counter terrorism official with experience fighting ISIS who requested anonymity in order to speak freely said “there’s value in pushing violent extremists off platforms that have the widest audiences”, while accepting that doing so would not completely silence the extremists. “But it will make them harder to be found and, even more importantly, to stumble upon casually.”

But, Amarasingam said, the “truly committed” found a way back into the networks online, or in the physical world — including the territorial Caliphate ISIS had for a while. “Die-hard supporters are already plugged into the network, usually in private groups anyway. They usually were able to keep in touch. People studying this stuff just lost visibility”, he said.

What will happen as the far-right replicates that pattern now is an urgent question in the United States, where extremists went to Parler, and now will perhaps migrate to Gab — less popular platforms, where minimal moderation permits an information atmosphere of often dizzying and sometimes violent mistruths. (Indeed, at the time of writing, Gab was promoting itself on Twitter with Exodus’ biblical verse about “letting my people go.”)

Amarasingam said a sustained approach against even ISIS’s more advanced networks online did have a significant impact. He noted a Europol campaign in November 2019 against ISIS extremists on Telegram — an encrypted messaging app that many far-right extremists in the US are reported to be moving to now. The pressure forced supporters onto other apps, which quickly kicked them off too. The strategy worked, reducing significantly the space for ISIS on Telegram because the effort was sustained. It might again too with the far-right, he said.

“Their reach will be diminished, their ability to form a real community online will be crippled, and they will spend most of their time simply trying to claw their way back as opposed to producing and disseminating new content” he said, dismissing the idea advanced by some experts that allowing extremists to air their views among a platform mostly inhabited by moderates might temper their behaviour. “Keeping neo-Nazis chasing their tail instead of barking at the rest of us is always a good idea”, Amarasingam said. He noted smaller groups of more radical extremists are also more easily and profitably infiltrated by law enforcement.

One factor that could make it harder for platforms to take action against the far-right is that some studies have suggested its online profile is less blatant than ISIS’. Professor Maura Conway at Dublin City University, who has extensively studied far-right extremism online, said their propaganda was often much less explicit in terms of its message and branding and was therefore harder to block or stop. It doesn’t, for example, have something like the black flag that was ubiquitous among ISIS supporters, or images of masked militants in fatigues.

“For example, in an online post, Patrick Crusius, the alleged El Paso shooter”, she wrote, “described the purpose of his attack as warding off the ‘Hispanic invasion of Texas’, which is a commonplace talking point on the US president’s preferred television station, Fox News, and a trope that Trump himself has employed repeatedly.”

Conway added this high-profile endorsement shifted the “Overton Window” of ideas considered acceptable in public, and made it harder to “respond effectively to right-wing extremist content …because to do so will increasingly be framed as reflecting a political bias against the right more broadly.”

Money is another complicating factor. Conway noted that far-right content also seemed profitable, drawing, according to her research, greater numbers of followers (and so eyeballs for advertisers) than ISIS content — on average about six times as many, when comparing followers of ISIS to far-right Twitter accounts. “The possibility for some platforms to profit from extreme-right activity is considerable”, she wrote.

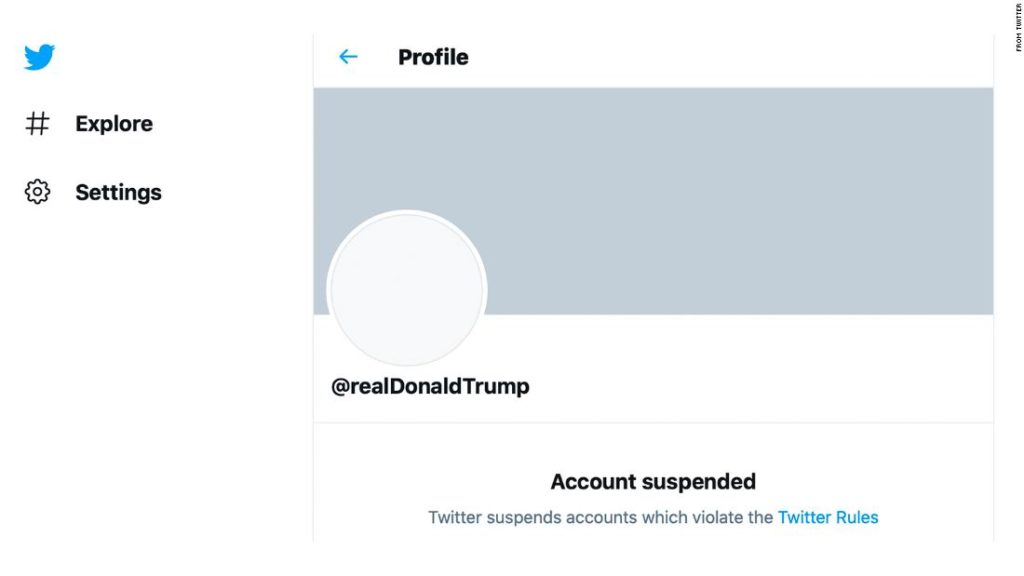

And the de-platforming of the world’s most powerful man presents a new challenge. President Trump’s office theoretically provides the largest platform in the world whenever he should choose to use it: in mainstream media, press statements, or the White House briefing room. But it may have been the raw nature of @realDonaldTrump that made it so popular, said Conway.

“It was precisely the sense that one was getting the US President’s unfiltered views via his Twitter account which made the @realDonaldTrump account so compelling to so many”, she emailed. Conway said other platforms were similar to Twitter, but none a precise replica, so she would not discount the possible impediment of Trump’s “personal learning curve …in switching to a new platform.”

Other toxic personalities have almost vanished after being deplatformed. The urgent question the US will learn the answer to in the weeks ahead is whether a historic figure — like an ex-president — can still influence through the internet when his many millions of followers have been scattered into an online netherworld.

In 2021, with the trillions our online lives are worth, there is little blunter indictment of the mess we are in online that — when faced with this high-stakes, existential question for democracy and the safety of Americans — officials and tech giants do not have a ready answer.

You may also like

-

Afghanistan: Civilian casualties hit record high amid US withdrawal, UN says

-

How Taiwan is trying to defend against a cyber ‘World War III’

-

Pandemic travel news this week: Quarantine escapes and airplane disguises

-

Why would anyone trust Brexit Britain again?

-

Black fungus: A second crisis is killing survivors of India’s worst Covid wave