The bottom line is it’s not easy to shed fresh light on a character who jumped so flamboyantly into the spotlight, and shuffled, ducked and dived to make sure he stayed in it. Enter, Ken Burns.

Now he has turned to Ali. Stretching eight hours (split into four episodes), “Muhammad Ali” took seven years to complete and features interviews with close friends, family, experts and cultural figureheads, selections from over 15,000 photographs and intimate footage that even Ali’s daughter Rasheda had not seen before. So yes, you could call it comprehensive. But still the question: Why?

“He’s the greatest athlete of the 20th century,” Burns tells CNN. “I’d be happy to sit on a barstool and argue that he’s the greatest athlete of all time — period, full stop.

“His life and his professional life intersected with all the main issues of the second half of the 20th century, that has to do obviously with sport and the role of sports in society and also race and politics and faith and Islam and war … He’s just the most compelling figure in all of sports.”

The director shares he has a neon sign in his editing suit that reads, “it’s complicated.” The same applies to Ali’s life. Alongside the familiar heroics, Burns gives the ugly side of Ali — the bullying, the promiscuity — ample space. “There’s no message” to the documentary, he insists, “we’re in the history business.”

“All of human life is complicated and contradictory and sometimes controversial, but there’s a majesty to this particular life, and I don’t think I’ve met an American as filled with the kind of spirit and sense of purpose as (Ali),” says Burns.

Walking through Ali’s life is a well-trodden path for boxing fans, but by dint of the volume of material Burns had to hand there are still some surprises. Here’s some lesser-known Ali trivia from the series.

Ali’s fear of flying was so extreme he once wore a parachute

When a young Cassius Clay traveled from Louisville to San Francisco for Olympic trials, so scared of flying was the amateur boxer that he bought a military parachute and wore it on the flight. When he won the competition, he pawned one of his prizes, a watch, to pay for a train ticket home instead.

Ali’s corner once put ice cubes down his shorts mid-fight

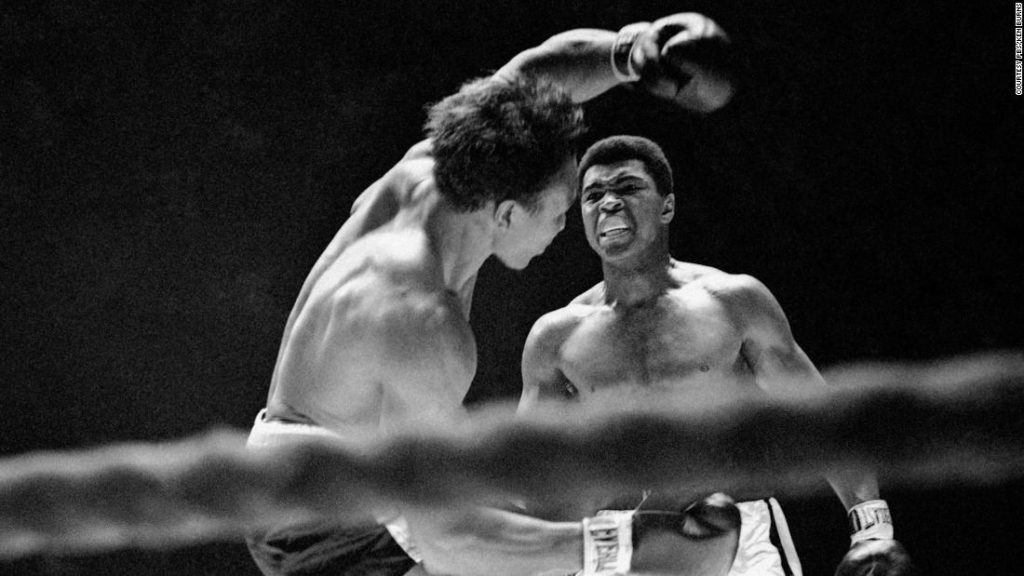

Fighting Henry Cooper in the UK in June 1963, then-Clay famously took a huge left hook seconds before the end of the fourth round. The bell arrived just in time for the American, whose corner did everything they could to wake him up for the next round. That meant smelling salts wafted under his nose and ice cubes down his shorts. It worked — he came back swinging and won in the fifth when the referee decided Cooper was too badly cut and bloodied to continue.

Before their bitter rivalry, Ali and Joe Frazier first met as friends

A young Frazier was 14-0 when he walked into an Ali training session and introduced himself. Ali said he’d fight the up and comer in two years if he kept on doing what he was doing and sent Frazier off with an autographed photo. It took longer than that, but by March 1971 the two undefeated boxers finally met.

Racists once sent Ali a decapitated dog in the mail

Ali’s legal dispute over his refusal to fight in the Vietnam War is well raked over in Burns’ documentary, including the horrific racist vitriol the boxer faced as a result. Convicted for draft evasion in 1967 and stripped of his boxing license and title, Ali was forced into the boxing hinterlands in his prime years. Ahead of his 1970 comeback fight against Jerry Quarry in Atlanta he was sent a box with a decapitated black dog inside and a note that read, “We know how to handle black draft-dodging dogs in Georgia.” Ali’s status as a conscientious objector would ultimately be vindicated when the Supreme Court unanimously overturned the conviction 8-0 in 1971.

When Ali lost to Frazier, Muammar Gaddafi declared a day of mourning

He was once gifted a boxing robe from Elvis Presley

And it was pure 70s Elvis. Ali wore the robe for his March 1973 fight against six-foot three-inch former marine Ken Norton. White and covered in jewels and with blue lettering on the back reading “People’s Choice,” the gift did not prove a good luck charm, with Norton inflicting Ali’s second professional loss.

Zaire’s Mobutu Sese Seko confiscated George Foreman’s passport in the lead up to “The Rumble in the Jungle”

After spending all that money financing “The Rumble in the Jungle,” the 1974 mega-fight between Ali and Foreman in Zaire (today, the Democratic Republic of Congo), dictatorial leader Mobutu wasn’t going to let anything stop it. Ali and Foreman both trained in Zaire in separate camps ahead of the fight. When Foreman was cut above the right eye in a sparring session, his doctor said it would take weeks to heal and called for a postponement. The boxer wanted to fly to France or Belgium for a second opinion, but Mobutu said no — he’d reportedly confiscated his passport. The fight was postponed by just over a month and both boxers stayed put.

By the end of his career, Ali was dying his hair

Even the most casual boxing fans know Ali kept boxing for too long, his body needlessly taking punishment long after his reputation as The Greatest was assured. But by 1980, when a 38-year-old Ali got in the ring with Larry Holmes, he was showing his age and dying his hair black to conceal the gray. It didn’t roll back the years — Ali was pummeled by Holmes. “It was like watching a friend get run over by a truck,” sportswriter Dave Kindred tells Burns.

He was a dab hand at magic

Ali met Fidel Castro in 1996, by which point the former champion was largely unable to speak due to the onset of Parkinson’s disease. He was still an entertainer however, and so performed magic tricks for the Cuban leader. But, believing it went against Islam to deceive, Ali showed Castro exactly how he’d done them straight after.

Ali originally declined to light the Olympic flame at Atlanta ’96

By the mid-90s Ali had taken a step back from the limelight, although he frequently traveled for humanitarian work. When the Atlanta Games asked him in secret if he’d light the Olympic flame, he said no at first, citing the frailties that came with his advancing Parkinson’s diagnosis. But his friend, photographer and biographer Howard Bingham, convinced him to, saying, “the world is saying thank you for all you’ve done over your life. There will be a billion people watching.” Ali’s surprise appearance remains one of the defining images of any Olympic Games.

Ken Burns’ “Muhammad Ali” debuts on September 19 on PBS.

You may also like

-

Super League: UEFA forced to drop disciplinary proceedings against remaining clubs

-

Simone Biles says she ‘should have quit way before Tokyo’

-

Kyrie Irving: NBA star the latest to withhold vaccination status

-

Roger Hunt: English football mourns death of Liverpool striker and World Cup winner

-

‘Every single time I lift the bar, I’m just lifting my country up’: Shiva Karout’s quest for powerlifting glory