How might architecture aid in solving the housing crisis and help build a more sustainable future? West of Ravenna, Italy, in the small town of Massa Lombarda, Mario Cucinella Architects has completed a prototype for a home that aims to do both, by combining some of the newest technology with the oldest housing materials. The dwelling, called TECLA, is the first 3D-printed home made from clay, and its founder, Mario Cucinella, hopes that its program design can become a viable option to house people who lack adequate housing due to financial issues or displacement.

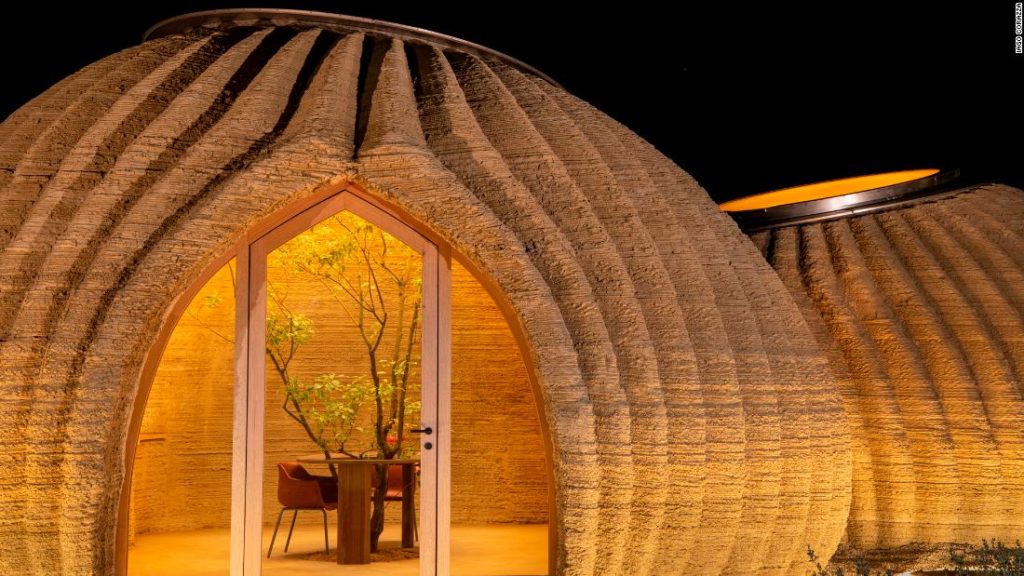

The twin-circular design of the TECLA prototype includes a bedroom, living room and bathroom. It is the first 3D-printed home made of clay. Credit: Iago Corazza

But while previous structures have been built using concrete or synthetic materials like plastic, TECLA — whose named is both derived from writer Italo Calvino’s fictional city of Thekla, and an amalgamation of “technology” and “clay” — was built from soil found at the site mixed with water, fibers from rice husks and a binder, the last of which Cucinella notes is less than 5% of the total volume. Cucinella believes this approach can be replicated in different parts of the world, using whatever local materials are available, and could be particularly helpful in underserved rural areas, where industrial construction materials may be harder to come by.

Printing with clay does have its drawbacks. It’s a much slower process than quick-drying concrete — the design can be printed in 200 hours but the clay mixture can take weeks to dry, depending on climate, according to Cucinella — and it also has height limitations (all-clay skyscrapers are not in the future).

Related video: See the first community of 3D-printed homes

However, the program’s flexibility of using available soil and its ease of construction means that TECLA could be well-suited to provide housing in many different countries. In 2015, Habitat for Humanity estimated that a staggering 1.6 billion people lack adequate housing, and UN-Habitat — the United Nations program for human settlements and sustainable urban development — estimates that by 2030, 3 billion people, or 40% of the world’s population, will require access to accessible and affordable residences.

“You can build this kind of house in many more places when you are not dependent on some specific product,” Cucinella explained in a video interview.

Tradition meets new technology

Building homes from earth, Cucinella pointed out, is not new. Adobe — made from a mix of earth, water and organic material — is one of the world’s earliest construction materials, known for its durability, biodegradability and natural insulation.

“The challenge was really using an old material in the history of architecture with new technology to find a new shape of house,” Cucinella said.

The project uses WASP printers to make everything from the structure of the home down to the furnishings. Credit: Iago Corazza

To that end, the Crane WASP printers mixed water with the local earth, and then printed the 60-square-meter (645-square-foot) TECLA prototype layer by layer, using an intricate lattice work pattern. The design features two circular spaces joined together, with skylights in each filtering light onto its textured walls. The residence includes a living area, a bedroom and bathroom. Its furnishings, including tables and chairs, can also be printed using WASP’s machinery, while components like doors and windows were installed post-printing.

But the idea behind TECLA isn’t necessarily to replicate the same home for any environment, but to adjust the design based on the location. “We are not producing one type of house that you can print and do it everywhere… Because, of course, it’s different if you design a house in the north of Italy, or… in the middle of Africa, or in South America,” Cucinella explained. “We adapt the house to different climates.”

A rendering of TECLA before it was printed shows what the bedroom could look like with a family living in it. Credit: Mario Cucinella Architects

Carbon-neutral goals

A rendering of what a TECLA community might look like. “If we look to the past, we can tap into the knowledge of how architects were able to design buildings with no energy for many, many centuries,” Cucinella said. Credit: Mario Cucinella Architects

Cucinella claims that TECLA is low-waste since its shell is biodegradable (extra fittings like doors and windows are not) and the construction process uses far less energy than building a standard home.

“When we talk about sustainability, I think we need to also think about the process of construction, because construction processes are very high-consuming and (make) high emissions of CO2 (carbon dioxide),” Cucinella said.

He believes we can learn from pre-industrial architectural design to make buildings that won’t harm the planet. “If we look to the past, we can tap into the knowledge of how architects were able to design buildings with no energy for many, many centuries,” he said.

The TECLA prototype is currently undergoing structural and thermal performance testing — an essential step before the project can be scaled. If it goes into production, Cucinella said he would happily live there, saying the materials evoke a sense of home and history.

“You get the feeling of something long ago from your memory,” he said.

Top caption: A photograph of TECLA at night.

You may also like

-

Afghanistan: Civilian casualties hit record high amid US withdrawal, UN says

-

How Taiwan is trying to defend against a cyber ‘World War III’

-

Pandemic travel news this week: Quarantine escapes and airplane disguises

-

Why would anyone trust Brexit Britain again?

-

Black fungus: A second crisis is killing survivors of India’s worst Covid wave