López Obrador’s coalition will be a significant voting bloc — but it will not reach what is known in Mexico as a “qualified majority.” This means that, on its own, it won’t have the necessary two-thirds majority required to change the constitution, which is something the president was hoping for.

Furthermore, projections from the same preliminary results suggest that a coalition of opposition parties could garner as much as 42 percent of the vote, which means they will be a strong opposition to the president and will be able to stop some of his most controversial proposals.

López Obrador’s party also scored plenty of state and municipal victories and his influence remains strong around the country, but he didn’t get the landslide he was hoping for.

The president lived his own self-fulfilling prophecy

For years, the president has talked about the threat of a hypothetical coalition of political parties that have little in common among themselves — other than antagonizing him. That coalition became a reality in this election.

The center-left PRI (Revolutionary Institutional Party), the conservative PAN (National Action Party) and the leftist PRD (Party of the Democratic Revolution) joined forces against the president, even though they make strange bedfellows.

Fernanda Caso, editorial director of Latitud312.com, a Mexican political website, says the idea was first mentioned publicly by the president himself. “I believe these coalitions, in great measure, came about because of the polarization generated at the presidency and by the presidency. Let’s remember that the first one to mention it as a conspiracy theory […] was the president,” Caso told CNN. “He also was the first one to talk about a referendum that would be held at the same time as the intermediate election,” Caso said.

In very general terms, the election was about López Obrador, his policies and his vision, says former Mexican Foreign Minister Jorge Castañeda. “What’s important is that the result can indeed be seen as a referendum on president López Obrador. He didn’t lose in an overwhelming way, but he didn’t win,” Castañeda told CNN.

Coalitions may not endure

The PRI, PAN and PRD have very little in common other than making sure the president doesn’t get free rein for what’s left of his six-year term, which ends in 2024. But neither does PVEM (Mexican Green Ecologist Party) have much in common with Morena, despite their current alliance.

These loosely created coalitions could suddenly bust (and even perhaps in the near future), depending on the political issues at hand. This could leave political power fragmented in Mexico, which is what the opposition hopes for PVEM-Morena.

The election was mainly peaceful

On his morning press conference Monday, the president made reporters chuckle when he said that “those who belong to organized crime, in general, [behaved] well.” It was meant as a joke, of course; but organized crime and gun violence in Mexico are no joke.

Up until the day of the election, 96 politicians and candidates had been murdered in Mexico since the beginning of the campaigns in September, according to risk management firm Etellekt. And the number of homicides around the country has continued to rise during López Obrador’s presidency.

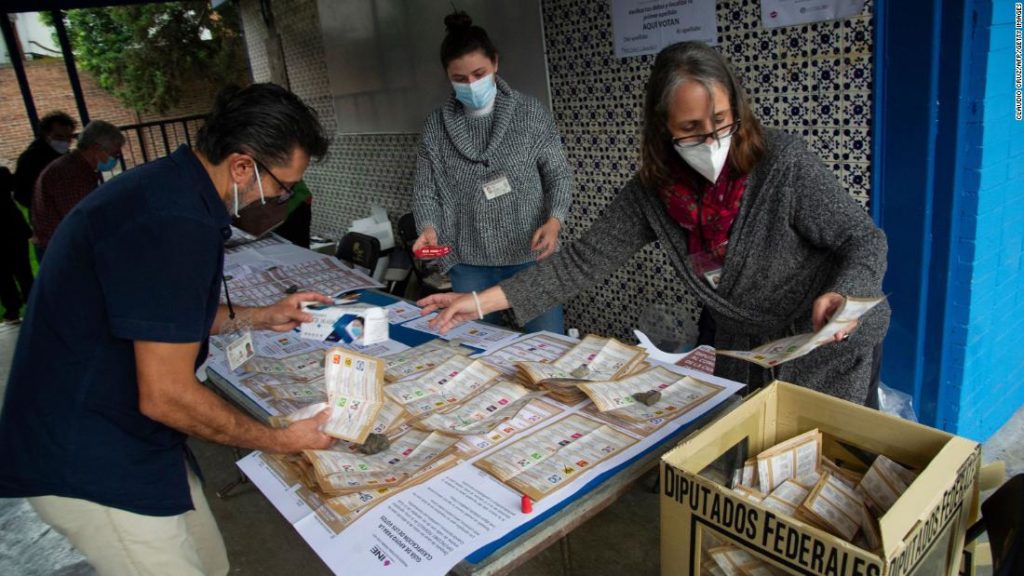

What the president meant was that, in spite of the challenge that criminality poses in Mexico, Sunday’s electoral authorities were able to organize and hold the largest election in the country’s history as planned. There were isolated incidents that marred the election, like the human remains found at two polling places in Tijuana and the fact that polls had to close early in Sinaloa state due to threats; but in general, Mexicans were able to cast their ballots unimpeded by anything but long lines in some places.

Mexican democracy was strengthened

In some places, people stood in line for two hours or more. Those interviewed by CNN said they were engaged because the future of their country was at stake. Others told us that they wanted democracy strengthened. Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa, winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, once described Mexico as “the perfect dictatorship,” due to the fact that a single party (the PRI) held power for more than seven decades, ruling with an iron fist.

No democracy is perfect. But after Sunday’s election, a turn towards any party’s complete rule in Mexico seems less likely.

You may also like

-

Afghanistan: Civilian casualties hit record high amid US withdrawal, UN says

-

How Taiwan is trying to defend against a cyber ‘World War III’

-

Pandemic travel news this week: Quarantine escapes and airplane disguises

-

Why would anyone trust Brexit Britain again?

-

Black fungus: A second crisis is killing survivors of India’s worst Covid wave