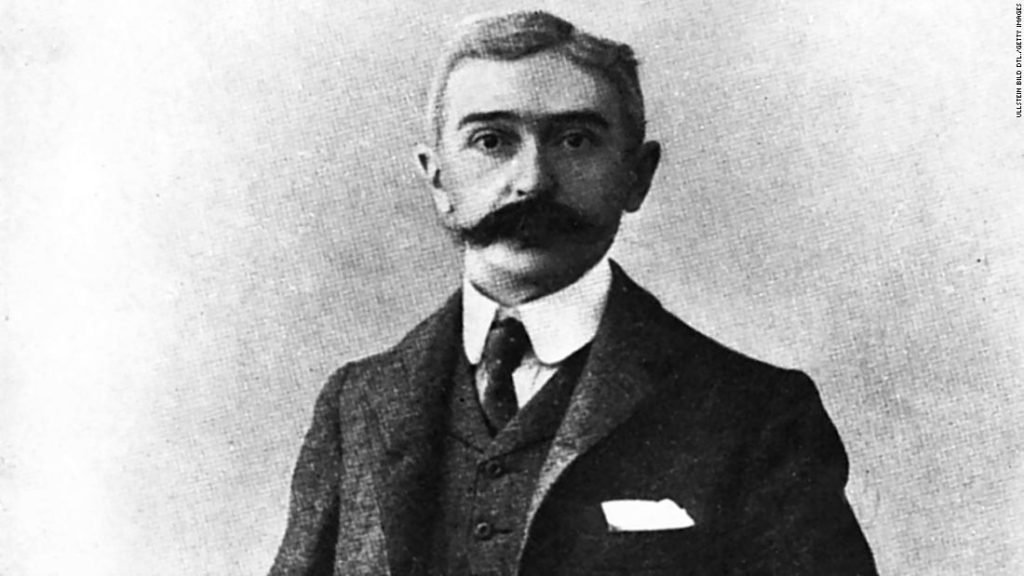

The day had been meticulously planned. After years of research, the 29-year-old baron would go public with his idea to revive the Olympic Games of Ancient Greece in the modern era. He’d chosen the old Sorbonne in Paris and the occasion of the fifth anniversary of the French athletics association to deliver his speech. It was a grand setting for a big idea: a sporting competition to bring nations together and learn from one another — to promote internationalism and world peace, no less.

The speech fell flat.

The audience was “not negative, but there was no support,” says David Wallechinsky, author and a founding member of the International Society of Olympic Historians. “He had a good speech and the wrong audience — an audience that was not sympathetic enough or open minded enough.”

“Coubertin realized that he hadn’t pulled it off, but he was persistent,” Wallechinsky adds. “He realized that idealism wasn’t enough. He had to get down to the nitty gritty and get the work done.”

The Olympic spirit

In 1892, France was yet to take organized sports to heart, says Stephan Wassong, an expert in the life of Coubertin and head of the Institute of Sport History at the German Sport University Cologne. Physical activity and organized sports were part of the military program but not the school curriculum, unlike the US and Britain.

But it was where sports could dovetail with his other passion that gave Coubertin’s idea an edge. A sworn internationalist whose writings detail an “awakening” at the World Fair of 1878, he became involved in the world peace movement, which like so many other movements, was centered in Paris at the time.

Having witnessed Englishman Hodgson Pratt propose an international student exchange to promote tolerance, at the 1891 World Peace Conference in Rome, “Coubertin took up this idea and … linked it with sport,” says Wassong.

This “wasn’t a popular concept,” says Wallechinsky, particularly among leaders in an age of colonialism and competition between European nations’ imperial ambitions. But Coubertin believed in his idea.

When the night at the Sorbonne came, the speech latched on to the popular revival of all things Hellenic, and used the reputation of the Ancient Olympic Games to support his idea. Coubertin praised the advancement of sport from Germany to Sweden, Britain to the US, lamented France’s slow start, and called sport the “free trade of the future.”

Sport was put on the same pedestal as the scientific and engineering innovations of the day: “It is clear that the telegraph, railways, the telephone, the passionate research in science, congresses and exhibitions have done more for peace than any treaty or diplomatic convention,” Coubertin said. “Well, I hope that athletics will do even more. Those who have seen 30,000 people running through the rain to attend a football match will not think that I am exaggerating.”

The speech “clearly laid down the educational fundamentals of the Olympic idea — of Olympism,” says Wassong, “and its mission to build a better world through sport.”

But though his lofty rhetoric fell on deaf ears that night, Coubertin had the will and the resources, and campaigned around Europe for his modern Olympic Games.

A complex legacy

He also said that the Olympic movement “needed constant updating, and to be adapted to the prevailing zeitgeist,” Wassong notes. So, while the movement is indebted to Coubertin, certain views he held should, by his own admission, be gladly left behind and disassociated from the Games.

“We’re going to have 11,000 or so athletes in Tokyo,” says Wallechinsky. “The vast majority — I would say 80% or more — will have no chance whatsoever of winning a medal, and they know it … But most of them are there to set a personal record, to set a national record, to do the best they can. I think that de Coubertin would have loved that.”

You may also like

-

Super League: UEFA forced to drop disciplinary proceedings against remaining clubs

-

Simone Biles says she ‘should have quit way before Tokyo’

-

Kyrie Irving: NBA star the latest to withhold vaccination status

-

Roger Hunt: English football mourns death of Liverpool striker and World Cup winner

-

‘Every single time I lift the bar, I’m just lifting my country up’: Shiva Karout’s quest for powerlifting glory